In the face of climate change and biodiversity loss, IPBES has called for transformative change—a deep shift in how societies relate to nature. One of the most powerful levers for that change is nature connectedness: the extent to which people feel emotionally and cognitively part of the natural world. But what are the societal factors that shape our relationship with nature?

Our latest research, published in Ambio and reported in The Guardian, takes a unique global perspective to help answer that question. Based on an analysis of data from over 60 countries and nearly 57,000 people (an impressive feat by the BINS survey team) it reveals that many nations are falling short. Nature connectedness isn’t just low in a few places; it’s systematically lower in wealthier, more urbanised, and business-oriented societies. And that matters, because nature connectedness is linked to our wellbeing, pro-environmental behaviour, and ultimately, the health of our planet.

To understand why this disconnect exists, we examined a wide range of macro-level factors—both tangible objective indicators (like urbanisation, biodiversity, and ease of doing business) and cultural subjective values (like spirituality, attitudes toward science, and views on societal change). The analysis combined statistical modelling, network analysis, and theoretical interpretation to identify which societal conditions and shared values are most strongly associated with nature connectedness. The results offer a compelling picture of how modern life shapes our relationship with nature—and where we might intervene to restore it.

What Shapes Our Relationship with Nature?

The findings show that urbanisation and ease of doing business are the strongest negative predictors of nature connectedness. These factors reflect a societal orientation toward efficiency, growth, and infrastructure—often at the expense of nature contact and biodiversity.

On the other hand, spirituality and a belief that society relies too heavily on science over faith emerged as the strongest positive predictors. These values suggest that nature connectedness flourishes where people seek deeper meaning and maintain a sense of reverence or emotional resonance with the natural world.

Interestingly, environmental organisation membership had little impact. This points to a deeper issue: nature connectedness is not just about what we do, but how we feel, think, and value our place in the living world.

A Global Pattern: The Disconnect of the Developed World

The rankings below tell a clear story. Countries like Nepal, Iran, and South Africa top the list for nature connectedness. Meanwhile, many affluent nations—including Germany, Canada, Japan, and the UK—sit near the bottom. The UK ranks 55th out of 61.

| The UK in Context: A Case Study in Disconnection

Within this global picture, the UK offers a stark example. Despite a rich tradition of nature writing and a strong conservation sector, the UK ranks near the bottom for nature connectedness. Why?

This doesn’t mean the UK lacks environmental concern. But it suggests that concern alone isn’t enough. To foster a deeper relationship with nature, we need to shift the cultural narrative—from control and consumption to connection and care. |

Nature Connection Rankings

| 1 | Nepal | 21 | Egypt | 41 | UAE |

| 2 | Iran | 22 | Slovenia | 42 | Italy |

| 3 | South Africa | 23 | Estonia | 43 | Poland |

| 4 | Bangladesh | 24 | Ecuador | 44 | Australia |

| 5 | Nigeria | 25 | Greece | 45 | USA |

| 6 | Chile | 26 | Lithuania | 46 | Lebanon |

| 7 | Croatia | 27 | Bahrain | 47 | Iceland (English) |

| 8 | Ghana | 28 | India | 48 | Ukraine |

| 9 | Bulgaria | 29 | Slovakia | 49 | Norway |

| 10 | Tunisia | 30 | Indonesia | 50 | Switzerland |

| 11 | Brazil | 31 | Cyprus | 51 | South Korea |

| 12 | Argentina | 32 | Hungary | 52 | Russia |

| 13 | Latvia | 33 | Kazakhstan | 53 | Ireland |

| 14 | Serbia | 34 | China | 54 | Saudi Arabia |

| 15 | Philippines | 35 | Thailand | 55 | United Kingdom |

| 16 | Colombia | 36 | Czechia | 56 | Netherlands |

| 17 | France | 37 | Portugal | 57 | Canada (English) |

| 18 | Malaysia | 38 | Romania | 58 | Germany |

| 19 | Malta | 39 | Austria | 59 | Israel |

| 20 | Turkey | 40 | Pakistan | 60 | Japan |

| 61 | Spain |

This isn’t just about geography or climate. It’s about culture, values, and systems. The global north tends to prioritise economic growth, technological advancement, and urban living—factors that, while hugely beneficial in many ways, appear to erode our relationship with nature.

So, what can we do about it?

Introducing the ‘X’ Model: Four Forces to Target for Change

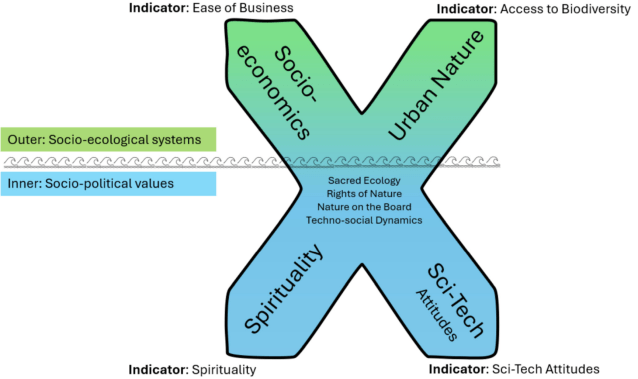

To help make sense of these findings, I developed a new conceptual framework—shaped like an ‘X’—to represent the key macro-level influences on nature connectedness. Each point of the X reflects a distinct force:

- Urban Nature: The impact of urbanisation and access to biodiversity. Cities often reduce direct contact with nature, but thoughtful design can restore it.

- Socio-economics: The influence of business systems, economic structures, and societal priorities. Ease of doing business was the strongest negative correlate—suggesting that pro-business regulations may come at the cost of ecological balance.

- Spirituality: The human search for meaning and connection beyond the material world. Countries with higher spiritual values tend to have stronger nature connectedness.

- Sci-tech Attitudes: The cultural balance between science and faith. A society that leans too heavily on technical solutions may overlook the emotional and existential dimensions of our relationship with nature.

The ‘X’ Model: Four Dimensions of Nature Connection

These forces interact in complex ways. The top half of the X—Urban Nature and Socio-economics—represents the outer world of infrastructure and policy. The bottom half—Spirituality and Sci-tech Attitudes—represents the inner world of values and beliefs.

Beyond the X: Towards Integration and Meaning

Tangible Systems, Intangible Needs

The ‘X’ Model highlights four macro forces shaping our relationship with nature—but the real challenge lies in how we integrate them. Urban Nature and Socio-economics reflect the tangible systems we build. Yet these systems often lack space for the intangible: spirituality, reverence, and meaning.

Sacred Urban Nature

Urban design must move beyond access to nature and toward nature-based neighbourhoods that bring engagement and meaning. This raises a deeper question: can urban nature be sacred? We respect cemeteries as places of rest, yet rarely extend that reverence to the places where nature lives. Initiatives like the Rights of Nature, which grant legal personhood to ecosystems, offer one way to bridge this divide—embedding spiritual and ethical value into the very fabric of urban planning.

Nature in Economic Systems

This also invites a rethinking of business and economics. If ease of doing business is a key factor in disconnection, then models that integrate nature into decision-making—such as biodiversity net gain or nature representation on company boards—can help shift the system. These approaches begin to treat nature not as a resource, but as a stakeholder.

Techno-Spiritual Futures

Sci-tech Attitudes and Spirituality pose a different challenge. As science and technology become ever more embedded in our socio-economic and urban systems, they increasingly shape how we live, think, and relate. But will they become a powerful source of meaning far removed from the natural world? How might spirituality evolve in a world of artificial intelligence and synthetic biology?

Reimagining Science and Spirit

This is not about choosing between science and spirit, but about reimagining their relationship. A techno-spiritual synthesis could help societies reconnect with nature—not by retreating from progress, but by infusing it with purpose. Concepts like sacred ecology, embodied design, and relational technologies may offer pathways forward—where innovation is guided not just by efficiency, but by empathy and reverence.

Rethinking Metrics and Meaning

The study also found that Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) scores are negatively correlated with nature connectedness. That’s a problem. If our sustainability metrics are anthropocentric and don’t reflect a relationship with nature, they are missing a crucial point.

A Framework for Thinking Differently

The ‘X’ Model offers a starting point. It’s not a final answer, but a framework for thinking differently.

Richardson, M., Lengieza, M., White, M. P., Tran, U. S., Voracek, M., Stieger, S., & Swami, V. (2025). Macro-level determinants of Nature Connectedness: An exploratory analysis of 61 countries. Ambio.