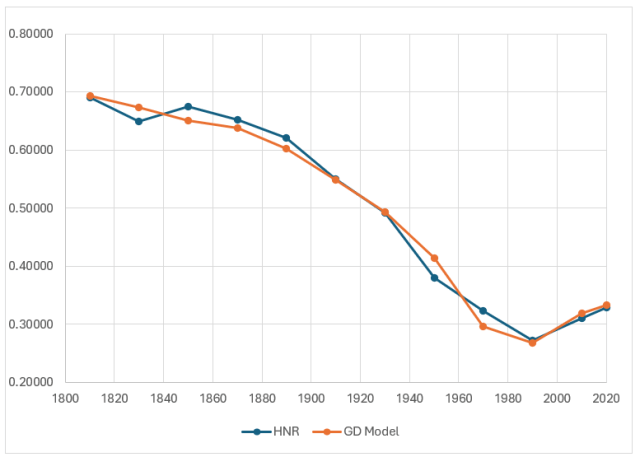

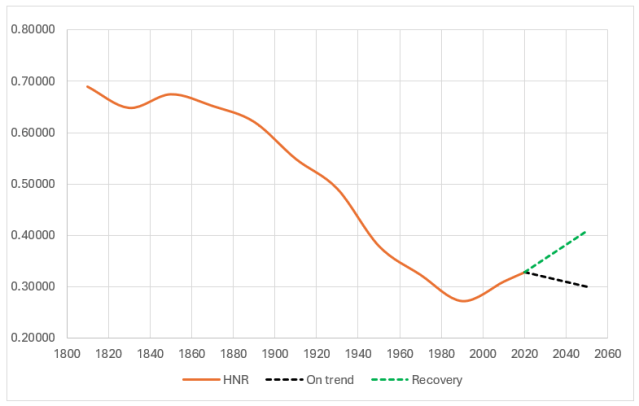

Over the past year I’ve been focussing on the bigger picture of nature connection, what factors explain differences between nations and over 200 years? I looked at long-term trends in a paper in Earth last summer, then differences between nations in Ambio in November, followed by trends again earlier this week in Sustainability Science. The fourth paper in that series (just one more to come!) has just been published in Biological Conservation.

Although there’s global recognition that solving environmental crises requires a new relationship and reconnection with nature there are differences in that relationship across nations and cultures. This paper takes a very broad approach using the largest regional grouping, the Global North and Global South which form two economic worlds. Aside from economic differences, there are also differences between the worldviews of the Global North and Global South which may well contribute to differing human–nature relationships. Therefore, in this paper we are interested in two key research questions:

- Does nature connectedness differ between Global North and Global South?

- If so, what factors might explain those differences?

Clearly, this grouping hides great differences between and within nations, yet the North–South grouping provides a useful way to investigate macro dynamics. It captures historically rooted economic and cultural contrasts that shape human–nature relationships at scale. Understanding similarity and differences on such a scale is important when considering global policy.

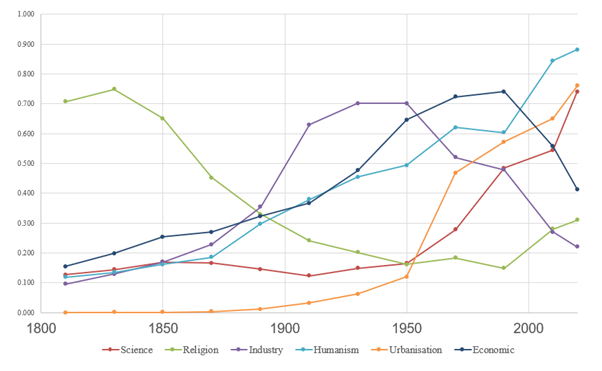

Using data from over 60 countries we looked at how a range of objective socio-economic (e.g. urbanisation, biodiversity, economy, income and technology) and subjective cultural indicators (e.g. values related to technology, science versus faith and spirituality) explain any differences in nature connection between the Global North and South.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, on average, nature connectedness was higher in nations of the Global South relative to the Global North. Given the grouping is based upon economic development, this fits with the proposal that the dualistic outlook of the North and how the perceived right of exploitation of natural resources for economic progress strengthened a sense of separation between humans and nature.

However, there was no difference in nature connectedness when controlling for economic differences. It was the indicators of subjective values that explained more variance in nature connectedness than the economic indicators, pointing to the key role of worldviews and values in shaping group-level nature connectedness. Together, the objective indicators explained 39.0% of the variance in nature connectedness between the north and south. Whereas the subjective indicators explained 53.2% of the variance.

It is also noteworthy that, when controlling for the North–South difference, several objective indicators were surprisingly non-significant despite appearing as significant indicators in previous research. For example, as a block, economic development factors, which have been identified as a negative predictor of country-level nature connectedness in several studies, were not a significant predictor after accounting for the North–South dichotomy. The fact that such a simple categorical dichotomy based largely on economic development managed to outperform a collection of continuous measures of the very same suggests that economic factors may not fully explain the underlying differences that contribute to the nature-connectedness disparity.

Similarly, biodiversity, which has likewise been identified as a significant predictor of country-level nature connectedness, was a non-significant predictor of nature connectedness when we controlled for the North-South dichotomy. Again, this suggests that some other factor (e.g., cultural differences, in this case) may explain differences in the human–nature relationship between North–South. One important consideration is that for many Indigenous cultures, connection to nature is not primarily through biodiversity or individual species, but through a deep relational bond with land itself. This differs markedly from Western perspectives, which often frame land in terms of ownership or resource value.

So what does explain the North–South dichotomy?

Although the North–South dichotomy is largely based on economic development, this study suggests there’s a need to consider other dimensions on which the regions differ. Spirituality showed a significant positive relationship with relationship to nature connectedness. Attitudes towards science and faith also played a role. Specifically, a stronger belief that society is too dependent on science over faith was associated with higher nature connectedness. In the Global North, people are more open to depending on science over faith. In contrast, the openness to dependence on faith over science in the Global South is, instead, accompanied by a stronger relationship with nature.

Natural Disasters

It’s interesting to note that vulnerability to natural disasters had a significant, negative impact on nature connectedness, yet both are significantly lower in the Global North—whereas in the Global South, the human–nature relationship is stronger, despite increased exposure to events such as flooding, storms, drought and earthquakes. This inconsistency may, in fact, highlight the strength of worldviews, values and spirituality compared with environmental factors. That is, while this negative correlation implies that one would expect nature connectedness to be lower in the Global South (where natural disasters are more common), nature connectedness is, indeed, higher in the south. Considering that no other environmental variables predicted nature connectedness, the most plausible explanation is that cultural supports, such as relational and spiritual interpretations of nature, buffer against the negative effects of environmental harm.

The reason for the inconsistency notwithstanding, it is still worth recognizing the negative relationship between natural disasters and nature connectedness. With such events likely to increase with climate change—including in the North where the cultural supports are not as present—the negative relationship between exposure to natural disasters and nature connectedness could undermine efforts to renew the relationship with nature.

Conclusions

This research set out to explore how global differences in nature connectedness can inform a closer relationship with nature. The findings reveal a significant disparity in nature connectedness between the economically defined regions of the Global North and South, with the former generally exhibiting lower levels of connection. By exploring the global differences in nature connectedness, the results suggest that nature connectedness is not primarily a product of economic or environmental conditions, but is deeply embedded in cultural, spiritual, and value-driven contexts.

They point to the need for a multifaceted approach to reimagining human–nature relationships, one that addresses the adverse effects of disasters, draws on cultural and spiritual strengths, and better connects science and faith to foster a sustainable, interconnected worldview.

Richardson, M., Rocha, N. M. F. D., & Lengieza, M. L. (2026). How can global differences in nature connection inform new relationships with nature? Biological Conservation, 316, 111768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2026.111768

Earth image By Reto Stöckli (land surface, shallow water, clouds)Robert Simmon (enhancements: ocean color, compositing, 3D globes, animation)Data and technical support: MODIS Land Group; MODIS Science Data Support Team; MODIS Atmosphere Group; MODIS Ocean GroupAdditional data: USGS EROS Data Center (topography); USGS Terrestrial Remote Sensing Flagstaff Field Center (Antarctica); Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (city lights). – https://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view.php?id=57723, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=306260