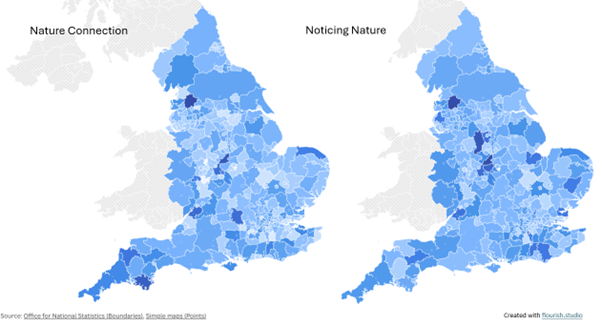

Discussions of nature connection often begin with access: how much green space people have, how close they live to it, and whether they are urban or rural. Drawing on People and Nature Survey (PANS) data across England, this blog takes an informal look at how nature connection varies across cities, towns and counties. The patterns that emerge challenge simple urban–rural explanations and point instead to deeper social, cultural, and regional influences.

The relationship between noticing and nature connection

The data looks at how strongly people feel part of nature and how often they notice and engage with everyday nature. The correlation between the two was weaker than might be expected, just 0.17 between nature connection and noticing across the local authorities with over 300 survey responses. While individual‑level studies show that actively noticing nature is an important pathway to stronger nature connection, the relatively weak correlation between noticing and nature connection at the local‑authority level suggests that place‑based differences reflect broader cultural, social, and historical factors, not just how often nature is noticed. We’ll return to that later.

Nature connection rankings

First-up, the sample sizes for each place could lead to around 8% error, so ranking differences in connection less than 5 need to be treated cautiously. Even allowing for this uncertainty, Liverpool and Leicester are likely below City of London and Tower Hamlets. And Cornwall is probably the most connected county surveyed.

| Cities n > 300 | NC | Counites n > 300 | NC | ||

| City of London | 70.20 | Cornwall | 70.09 | ||

| Tower Hamlets | 66.96 | North Yorkshire | 64.72 | ||

| Stockport | 61.68 | East Riding of Yorkshire | 63.78 | ||

| Manchester | 60.90 | Wiltshire | 63.42 | ||

| Bradford | 59.56 | Dorset | 62.91 | ||

| Barnet | 59.23 | North Northamptonshire | 62.49 | ||

| Bournemouth | 59.12 | Northumberland | 61.56 | ||

| Sheffield | 59.00 | Somerset | 61.46 | ||

| Leeds | 58.74 | West Northamptonshire | 61.14 | ||

| Dudley | 56.83 | County Durham | 60.24 | ||

| Birmingham | 56.68 | Buckinghamshire | 58.33 | ||

| Nottingham | 56.57 | ||||

| Kirklees | 55.94 | ||||

| Bristol | 54.43 | ||||

| Liverpool | 52.89 | ||||

| Leicester | 51.59 | ||||

| Mean | 58.77 | Mean | 62.74 |

City Living

At first glance, the City of London’s score looks anomalous, it has a low level of green space per person. It’s an unusual area though with around 9000 residents who are likely to be high earners and have second homes outside London. They’re nature identities likely formed elsewhere, so nature connection levels are less likely to be an effect of the urban environment itself. So, the City’s high score should not be read as evidence that dense commercial urban form promotes nature connection, but rather as an illustration that strong nature connection can persist even in highly urbanised contexts under certain social and experiential conditions

Tower Hamlets neighbours the City of London. It too has a low level of green space per person, but a lot more people at high density. So, there may be more green spaces than that suggests. It is threaded by canals, docks, and river-edges and more biodiverse green roofs than any other London borough!

Tower Hamlets is a “Tree City of the World” and promotes urban greening, estate-level and community-led planting. I’ve read that it has communities with strong traditions of allotment growing and outdoor social life. Nature could well be more embedded in living rather than framed as “recreation” or “escape”.

We know nature connection varies from nation to nation and Tower Hamlets has the largest Bangladeshi-born population in England and Wales. Perhaps, that community brings culturally embedded ways of relating to nature with them.

The interaction between cultural scripts of nature, migration history, urban form, and everyday practice will be complex. In some places (Tower Hamlets, Bradford, parts of Stockport), these align to support nature connection; in others (e.g. Leicester), they do not. Lived nature connection depends on whether the local environment affords expression of those practices. People may value nature highly but have fewer opportunities to enact that value daily. They may experience nature as distant, managed, or regulated.

Rural and Urban differences

The mean difference between urban and rural areas of 6.8% is far lower than the variation across cities (36%) or counties (20%), so the rural/urban divide is too simplistic. Especially as some city areas score so highly. Although urbanisation is a strong factor in nature connection across several studies it shows that there are other important regional factors.

High nature connection is not simply the outcome of noticing more nature in everyday life; it reflects deeper meanings, identities, and practices that are perhaps weakly tied to perceptual attention. There was a period where nature connectedness was often framed through mindfulness, but this data, plus the more structural research last year helps show how individual connection is context‑dependent, historically produced and socially transmitted within and across generations. This helps explain why dense, highly managed urban areas can score as highly as rural counties.

Which brings us to Buckinghamshire which provides a useful counter‑example to simple access‑based explanations of nature connection. Despite extensive countryside and relatively high affluence, average nature connection scores are low. This may reflect the county’s role as a commuter belt, where daily routines leave little space for everyday engagement with nature, and where landscapes are often experienced as destinations rather than lived environments. In this context, nature is nearby but not necessarily meaningful, reinforcing the idea that sustained nature connection depends less on proximity and more on how nature is woven into everyday life and identity.

Noticing Nature

| Cities n > 300 | Noticing | Counites n > 300 | Noticing | ||

| City of London | 76.67 | Shropshire | 74.06 | ||

| Stockport | 73.88 | Cornwall | 73.99 | ||

| Dudley | 72.94 | Somerset | 73.08 | ||

| Tower Hamlets | 71.81 | North Northamptonshire | 70.26 | ||

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 68.70 | North Yorkshire | 69.94 | ||

| Bournemouth | 68.46 | County Durham | 69.46 | ||

| Manchester | 68.19 | East Suffolk | 67.61 | ||

| Derby | 68.09 | Wiltshire | 67.39 | ||

| Kirklees | 67.59 | Barnet | 67.27 | ||

| Barnet | 67.27 | Buckinghamshire | 66.74 | ||

| Bristol | 67.04 | West Northamptonshire | 66.68 | ||

| Wigan | 66.54 | Cheshire East | 65.76 | ||

| Leicester | 66.04 | Northumberland | 65.34 | ||

| Bradford | 65.91 | Dorset | 65.26 | ||

| Birmingham | 65.44 | East Riding of Yorkshire | 64.93 | ||

| Sheffield | 65.18 | ||||

| Liverpool | 65.09 | ||||

| Leeds | 65.08 | ||||

| Walsall | 63.10 | ||||

| Sandwell | 62.68 | ||||

| Coventry | 62.12 | ||||

| Nottingham | 61.77 | ||||

| Croydon | 60.41 | ||||

| Wolverhampton | 58.47 | ||||

| Mean | 66.60 | Mean | 68.52 |

For noticing nature, once again, the mean difference between urban and rural at 2.9% is far lower than the variation across cities (31%) or counties (29%). Given the weak relationship between noticing and connection at the place level there are other important factors that explain the differences. Places differ not just in how often people notice nature, but in whether those moments stick.

Noticing nature is a psychological mechanism that can be influenced by interventions to increase nature connection, but sustained nature connection depends on deeper structures. The persistence of nature connection at the level of places reflects deeper cultural and structural conditions, a pattern that mirrors my recent agent‑based modelling work on the emergence and decay of nature connection over time.

Cultural, social, and historical factors

Nature connectedness research has had a rapid growth over the last decade. As a field, it is maturing. The more reductionist, individual‑level focus was, and still is, necessary to establish a robust evidence base. My own more recent work has moved from viewing nature connectedness as an individual trait towards understanding it as an embedded phenomenon, explored through agent‑based modelling. In many ways, this marks a return to my ergonomics and human factors roots.

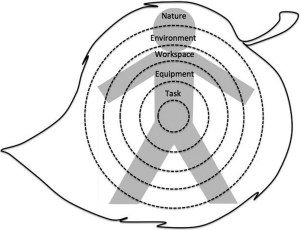

Those roots have always been present. One example is the reimagined ergonomics onion developed in 2017.

A nature connectedness informed, embedded model of ergonomics. Notes: Richardson et al., (2017); Adapted from Grey, Norris and Wilson (1987); Wilson and Corlett (2005).

Ergonomics, at its core, is concerned with the relationship between people and their environment, traditionally placing the person at the centre of the ‘onion’. The concentric rings represent interacting factors across solid boundaries, with the outside world treated as something external that we encounter. The adaptation above attempts to capture embeddedness by softening these boundaries and a larger shaded human form which reflects that experiences are not mediated across layers but are shared across factors.

From a nature connection perspective, the person does not reside at the centre. Instead, the self and the external natural world are integrated. The things we do, and the wider environment in which we do them, are part of our being. Being is not separate from the world; it is constituted through interaction with it.

Yet to understand nature connection, science often seeks to control and isolate factors, effectively reducing the number of layers in the onion. This is a necessary approach for understanding individual mechanisms, but it inevitably places complex realities to the side.

My recent research therefore focuses on simulating individuals and their dispositions within families, cultures, and environments shaped by urbanisation, education, and economic priorities. As with the regional patterns discussed above, nature connectedness becomes something that is experienced individually but shaped, scaffolded, and constrained culturally.

There is cultural inheritance, where some cultures transmit more holistic ontologies, moral standing for non‑humans, and seasonal, land‑based narratives, raising the population mean of nature connection.

There is everyday practice, where nature is part of food, work, worship, or daily movement rather than a recreational “escape”. In these contexts, nature connection becomes habitual rather than episodic.

There is environmental affordance, where those cultural scripts only persist if people can enact them and nature remains encounterable rather than abstract. Constraints such as urban design can suppress culturally inherited nature connection. Lower scores therefore do not imply weaker values, but weaker opportunities for expression.

The challenge now is to model these interactions and examine the levels of nature connection that emerge, and to test whether such simulations can reproduce the differences observed between local authorities. That is a study I hope to see published in the spring.

Conclusions

The data shows that nature connection doesn’t simply scale with rurality or green space. Instead, they point towards a more relational model where culture, stewardship, life history, and everyday engagement shape how people experience their place in nature, even in the most urban parts of England. Urban nature connection is compositional, not just spatial. Higher levels reflect who lives there and how they can relate to nature as afforded by what surrounds them. Culture sets the potential; place determines whether it can be realised. Understanding and modelling that interaction may be essential if we are to move beyond simple access‑based solutions and support enduring relationships between people and nature.