Over the past few years, I’ve often written about our failing relationship with nature. It’s now recognised that this issue lies at the heart of the environmental crises, but how do we solve it? What if we could simulate how that disconnection occurred? What if a computer model tuned by real world data could help us understand not just how we got here, but where we might be headed?

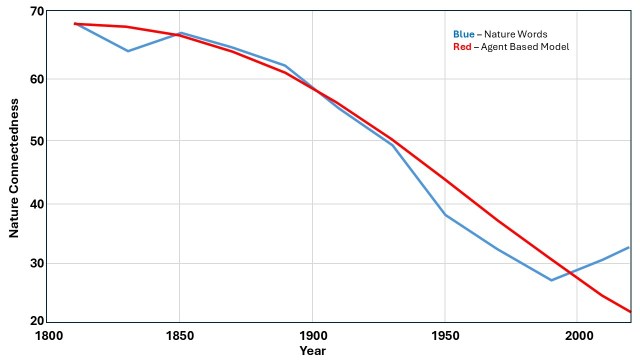

That’s exactly what my latest research published in Earth and featured in The Guardian set out to do. It uses a computer model to simulate the long-term decline in nature connection from 1800 to 2020 and tests it against real world data. Then it projects what might happen over the next century. It’s a story of urbanisation, intergenerational change, and the quiet erosion of everyday nature in our lives. But it’s also a story of hope, because it shows how transformative action could turn things around.

A Model of Human–Nature Disconnection

At the heart of the study is a simulation that models how people interact with their environment over time. It’s built on the idea of the extinction of experience—the cycle where loss of nature leads to lower connection, which can then get passed on to the next generation as shown in the conceptual framework below. This illustrates how nature connection is built from people’s engagement with nature, both within a lifetime through attention to nature and across generations through feedback loops. One feedback loop captures how engaging with our surroundings shapes our connection to nature during our lifetime, and another models how parents pass on their orientation to nature to their children.

The model simulates this and tracks individuals and families across an initially nature-rich landscape (see green dots below), simulating births, deaths, and changes in nature connectedness as nature depleted urban areas (red dots) expand, matching historical urbanisation data. Families (blue dots) come and go within a natural environment becoming more urban.

Simulation of living with increasing urbanisation. Families (blue dots) come and go within a natural environment (green dots) becoming more urban (red dots).

The model runs from 1800 to 2125 to test future scenarios. It’s not just about individuals—it’s about systems, generations, and tipping points. It captures how cultural and environmental changes ripple through time.

Model versus Nature Words

To test the model, a way to track nature connectedness over time was needed. But of course, we don’t have surveys from the 1800s. So I turned to culture. Specifically, I used the frequency of nature-related words in books—words like river, blossom, moss, and bough—as a proxy for how connected people were to nature. These words reflect what people noticed, valued, and wrote about. And when their use is plotted over time, a clear decline of around 60% is revealed. Particularly from 1850, a time when industrialisation and urbanisation grew rapidly.

Here’s the remarkable part: the model (red line), built from the ground up to simulate human–nature interactions, closely mirrored, with less than 5% error, the actual decline in nature word use, see chart below. Despite the uncertainties of using language as a proxy, the fit was striking. It suggests that the model is capturing something real about how our relationship with nature has changed. The model’s accuracy validates its ability to predict future trends.

Time-series plot of modelled nature connectedness (red line) and the nature connectedness target (blue line).

The modelled nature connectedness decline of 61.5% was very close to the 60.6% maximum decline of nature words in 1990. For context, in a cross-sectional survey of 63 nations, nature connectedness in the USA was 57.5% below the nation with highest level, Nepal, relative to the full range. This suggests the modelled decline is plausible.

However, the model missed the 8% uptick to 2020. This suggests either an issue with the nature word data since 1990, such as recent publishing trends for ‘nature writing’, or that the model may be missing societal factors that have positively influenced nature connectedness in recent decades.

There are a number of societal factors that are associated with levels of nature connectedness. Only one with a positive association with nature connectedness has seen a recent uptick, spirituality. Perhaps a growing need for spiritual fulfilment has driven an increase in nature connectedness, or nature word use. However, such changes would need to overcome the rapid increases in factors with a negative relationship, such as the rapid penetration of smartphone technology.

Either way, large national surveys running since 2020 show that nature connectedness is in decline, so recovery doesn’t seem to be underway.

What the Model Reveals

The model simulation reveals a steep decline in nature connectedness from 1800 to 2020, primarily driven by urbanisation and environmental degradation. However, the most significant factor is intergenerational transmission: as parents lose connection to nature, their children begin life with lower connection, creating cultural inertia that persists even if environmental conditions improve.

Crucially, calibration revealed that intergenerational transmission overwhelmingly accounts for the long-term decline, while the lifetime extinction of experience mechanism added only marginal refinement. This insight underscores the importance of early-life and family-based interventions in reversing the trend and highlights the deep-rooted, systemic nature of human–nature disconnection.

Into the Future

To explore how nature connectedness might evolve, the model tested a range of future scenarios involving three types of interventions:

- Urban greening: Increasing nature in cities by 50%, 100%, or 1000%, in the context of a tenfold rise in urbanisation since 1800.

- Nature engagement campaigns: Boosting attention to nature by 50%, 200%, or 300%, against a backdrop of a threefold decline in nature connectedness.

- Parenting and early-life interventions: Enhancing intergenerational transmission by 30%—a stretch target based on current interventions that typically yield 10% gains. This was phased in over 10 years and then held constant.

Changes to nature access and attention were scaled linearly from 2020 to 2050, then maintained through 2125.

The simulation revealed three distinct clusters of outcomes (see chart below):

- Continued decline: Scenarios with modest increases in nature access (50% or 100%) or attention alone failed to reverse the downward trend. These interventions, even in combination, were insufficient to counteract the system’s inertia.

- Holding steady: Some scenarios halted the decline but didn’t reverse it. This included the child-focused intervention alone, or combined with low-level greening and attention boosts. Even a 1000% increase in nature access alone only stabilised the trend.

- Recovery and growth: Only the most ambitious combined interventions—such as a 1000% increase in nature access paired with the child-focused strategy—led to a delayed but accelerating recovery post-2050. This illustrates how intergenerational transmission can shift from a vicious to a virtuous cycle.

These findings highlight the system’s deep inertia: even transformative interventions take decades to show results. This delay underscores the urgency of early, sustained action.

Importantly, these targets might be more achievable than they appear, a 1000% increase in nature to counteract a similar change in urbanisation is daunting. However, in the UK, people spend around 7% of their time outdoors—half of that in urban settings—and a median of only 4.5 minutes per day in green spaces. A tenfold increase would mean 35% of the day outdoors or just 45 minutes in nature rich places—ambitious, but within reach.

Why It Matters

This isn’t just an academic exercise. Nature connectedness is increasingly recognised as a causal factor in the environmental crises we face today. When people feel disconnected from nature, they’re less likely to care for it. Conversely, promoting stronger nature connectedness can be a powerful strategy for transformative change (IPBES, 2024).

The findings presented here support the report’s conclusion that deep, systemic change is urgent, necessary, and challenging. The model reinforces this, showing that transformative changes in intergenerational transmission are required. The model highlights the scale of transformation required—not just in environmental conditions, but in cultural and familial dynamics—to reverse the long-term erosion of our relationship with nature.

Targeting nature connectedness is becoming a focus for policy proposals, but if we don’t understand how nature connectedness diminished in the first place, how can we know which direction to head in?

This research helps answer that. It shows that disconnection didn’t happen overnight—it was shaped by urbanisation, cultural shifts, and intergenerational change. And it won’t be reversed overnight either. The model shows that recovery takes time, and that early-life experiences, education, and urban design are key.

It also highlights the importance of feedback loops. Once disconnection sets in, it becomes self-reinforcing. But the same is true in reverse: once enough people begin to reconnect, the system can tip toward restoration. That’s the power of cultural change—it can cascade.

Recommendations

So what does this mean for policy, education, and everyday life? The model points to several key recommendations:

Strengthen Intergenerational Transmission

Support parent and child engagement with nature through nature-based programs, school curricula, and family policies. Encourage nature-focused parenting resources, public campaigns, and peer networks to enhance cultural transmission.

Transform Urban Greening and Access

Prioritise biodiverse, accessible greenspaces in urban planning. Integrate nature access across public services—education, health, housing, and transport—to increase everyday engagement with nature. Back community-led initiatives to foster local stewardship.

Monitor and Evaluate Nature Connectedness

Expand national and local tracking systems. Embed nature connectedness indicators into wellbeing and environmental reporting. Use real-time data to inform adaptive, evidence-based policy.

Key Conclusions

This study reveals that reversing the decline in nature connectedness requires more than environmental improvements—it demands systemic, long-term cultural change. The model highlights intergenerational transmission as the dominant force sustaining disconnection, making early-life and family-based interventions critical. Despite ambitious interventions, recovery is delayed by deep system inertia, with meaningful change not emerging until after 2050. This underscores the urgency of acting now to avoid further entrenchment of disconnection. The model’s close alignment with historical cultural trends also validates its relevance, showing that environmental exposure, attention, and familial influence can explain centuries of change. Together, these findings call for urgent, sustained, and multi-level action—combining urban design, education, and governance—to restore our relationship with nature.

Richardson M. Modelling Nature Connectedness Within Environmental Systems: Human-Nature Relationships from 1800 to 2020 and Beyond. Earth. 2025; 6(3):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6030082