By Dr Carly Butler

Following our previous handbooks, which offer an introduction to connecting people with nature, and helping organisations connect with nature, we are delighted to launch our newest handbook – the Nature Connected Communities Handbook, a guide for inviting communities to notice, engage and relate with the more-than-human world, for closer community-nature relationships.

There is growing activity and interest in nature-based community initiatives around the United Kingdom, which help people connect with each other, their local areas, and with the natural world. Such initiatives take many forms, and can include community events, rewilding a patch of grass in a suburban street, or developing a community garden, through to creating a greener city, and everything in between. As well as benefitting individual and community wellbeing and resilience, such initiatives can improve nature’s wellbeing and resilience by boosting biodiversity and creating more space for more nature. Crucially, these initiatives can also help strengthen people’s relationships with the rest of nature, improving nature connectedness which is associated with even greater benefits for personal, social and environmental wellbeing.

The handbook includes some practical guidance and inspiration with tips and case studies from those who are designing and delivering excellent green community initiatives and generously shared their expertise and experiences with us. We also link to some brilliant online resources and networks that offer support for help nature-based community projects. With improving human-nature relationships being at the heart of what we do in the Nature Connectedness Research Group at University of Derby, our particular focus for the handbook was on how such projects can spread and deepen community nature connectedness, by helping communities grow emotional and meaningful relationships with the rest of nature.

Research demonstrates how important an individual’s sense of nature connectedness is for their own wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour. A focus on growing nature connectedness at a community level has benefits that go beyond the individual, supporting community wellbeing and larger scale pro-nature values and actions. When communities share a sense of feeling a part of the rest of nature, we edge closer to the social tipping points for transformational change in human-nature relationships.

As Aldo Leopold noted over 75 years ago, humans are part of a wider community of life, including non-human beings. A deeply nature connected community is one that recognises humans and more-than-humans are all citizens of shared common spaces, in which people and nature flourish together. Such communities are based on relationships and a sense of kinship between people and the rest of nature, with practices of love, care and respect between all lives at its core. The human members of nature connected communities:

* Understand that we are part of nature, not separate from it.

* Grow deeper emotional connections with animals, plants, and other living things.

* Engage with the natural world in ways that help all forms of life.

* See animals, plants, and the environment as members of our shared community.

* Work to improve the wellbeing of both people and nature together.

The Nature Connected Communities Handbook explores how green community initiatives can nurture relationships between humans and the rest of nature that support the recognition and celebration of the interconnectedness of humans and the rest of nature within communities. We were guided by the number one message from those organisations involved in initiatives on the ground: listen to communities. A successful community project has to reflect the needs and interests of communities themselves. As such, we offer the guidance as a basis for exploration and inspiration, for those communities interested in supporting emotionally meaningful relationships between humans and the rest of nature. The offerings will hopefully inspire reflection, discussions and playful questioning into the spaces between human and non-human community members.

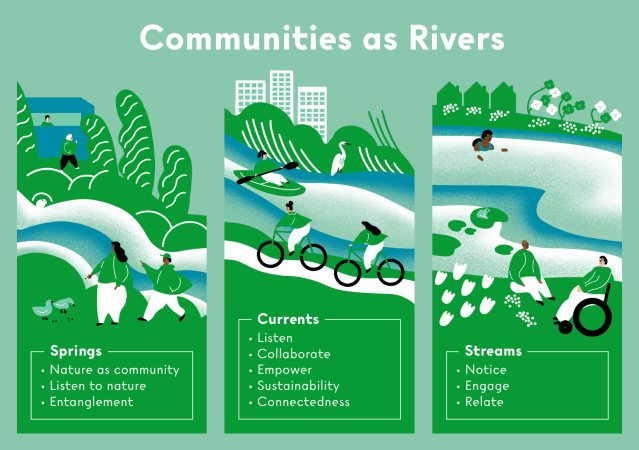

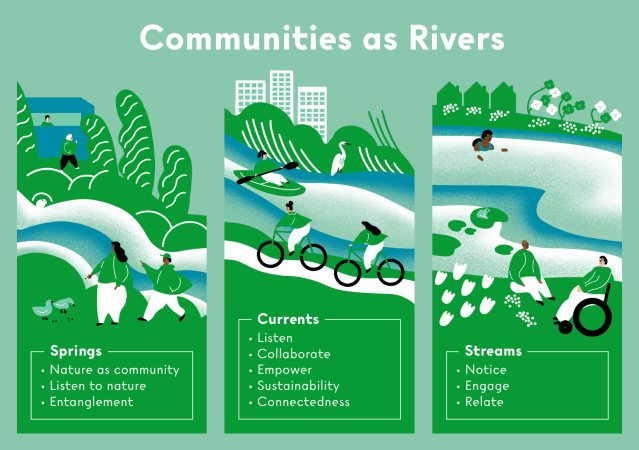

Community as River

We draw on a metaphor of a community as river, that flows together as one. Springs are the source of nature-connected communities, the principles from which an initiative begins. Currents are how they move, the things that enable easy flow around obstacles and blockages within an initiative. Streams carry human and more-than-human community members together into closer relationship – these represent the modes of human-nature interaction that a community initiative can nurture. The three streams are Notice, Engage and Relate which flow progressively towards a recognition of communities as made up of both human and more-than-human citizens.

Springs: Principles of nature-connected communities that recognise the commonality of humans and the rest of nature.

Currents: Practical tips for connecting communities with nature and supporting movement and flow within projects and hubs, based on the experience and knowledge of those on-the-ground, delivering successful green community initiatives.

Streams: Design for a nature connected community by creating opportunities for people to notice nature, engage with nature using the pathways to nature connectedness, and relate with non-human community members.

Resources

The handbook comes with a collection of resources:

- A workshop guide with some suggestions for exploring the ideas in the handbook with community groups

- Urban Safari – a printable nature-noticing activity that can be used in any environment at any time of year focused on sensory, emotional and meaningful engagement with nature

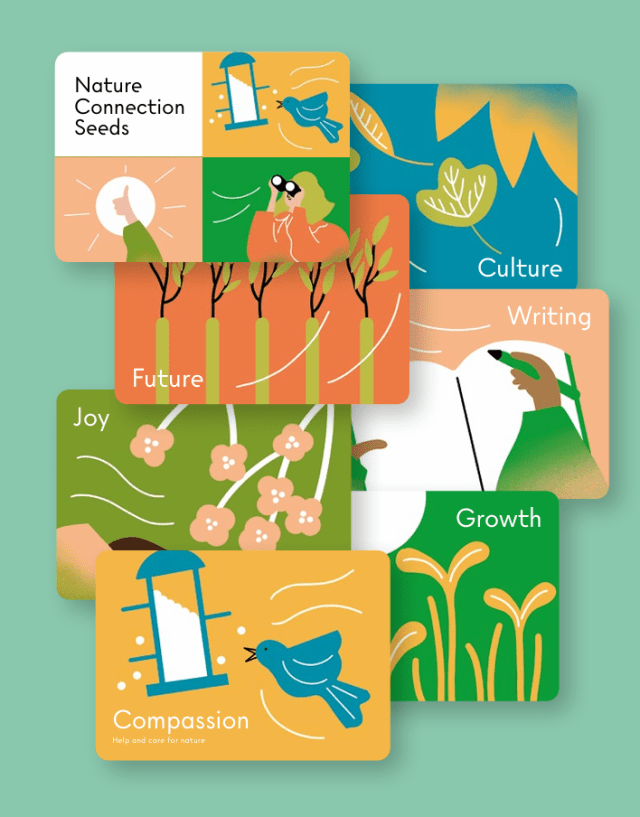

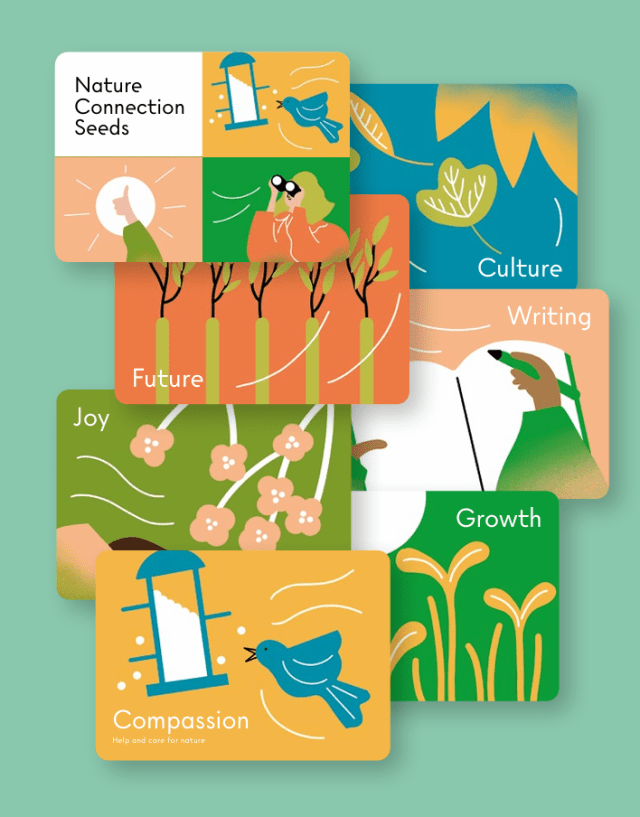

- Nature Connection Seeds – a printable deck of cards that can be used flexibly to design and develop nature connection projects and activities, with some suggestions for use

- External resource hubs and networks – signposts to support and practical guidance for delivering green community projects.

Case Studies

As well as inviting those leading inspirational green community projects to share their top tips for creating nature-connected communities (the Currents), we gathered some case studies to showcase their innovative and successful initiatives. The case studies illustrate the power of gardens, woodlands, art, nature connection activities and green hubs to connect communities with nature, and emphasise the importance of listening to communities, co-design, inclusion, systems-based approaches, and bringing life into nature-depleted spaces.

Share your examples!

With nature-based community initiatives continuing to spread and grow, we want to collect examples of projects and community-based events and activities that help support nature connectedness so they can be shared to inspire others. Let us know of creative, fun, and powerful ways of encouraging communities to notice and celebrate the nature around them, to engage with the pathways to nature connectedness for sensory, emotional, aesthetic, meaningful and compassionate moments with nature, and to consider the perspectives and rights of the more-than-human. Whether it is an example you’ve seen elsewhere or something you’ve delivered yourself, please visit our webpage and add to the public database: https://www.natureconnectedness.net/nature-connected-communities

Thanks

Our thanks go out to the fabulous Open and Honest for design and Catherine Chialton for illustration, who have – once again – made the handbook look beautiful. Thanks also to those who attended our Nature Connected Communities workshop in May 2024 and contributed to the tips collated here, particularly those who shared their projects and initiatives. Thanks to Lara Pike for help with the workshop, and a huge thank you to Wates Family Enterprise Trust who funded and supported this work.