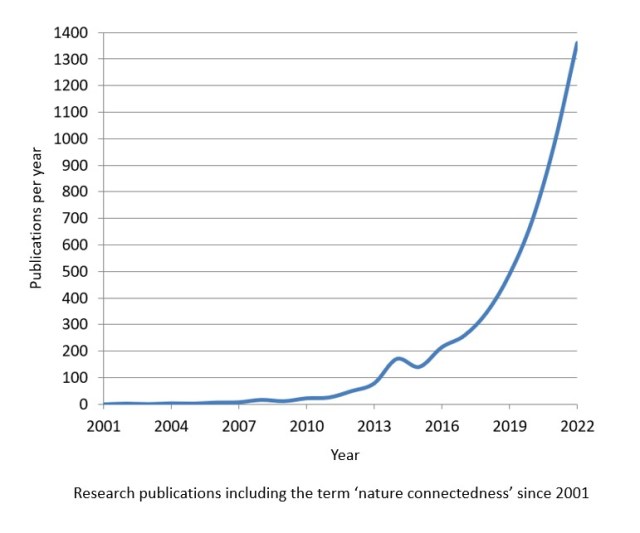

Major environmental institutions around the world are realising that a sustainable future requires a new relationship with nature. Recognising that the human-nature relationship is a tangible target for change that drives behaviour. The latest example is ‘Exiting the Anthropocene? Exploring fundamental change in our relationship with nature’, a milestone briefing from European Environment Agency, which is informed by our nature connectedness research and the biodiversity stripes concept – pushing environment science-policy thinking beyond what has gone before. This recognition and progress is driven by research, as demonstrated by the UN commissioned Stolkholm+50 evidence review. The increase in nature connectedness research since 2001 is remarkable, with work in this area increasingly being published in the world’s leading journals. Keeping up with the research is a challenge and in the past few weeks alone several particularly interesting papers have been published. Covering whether nature connection is weakening over time, green space versus connection, nearby nature versus excursions, the link between connection and behaviour, urban nature connection and how, despite the evidence, designing for human–nature connection is yet to become mainstream.

There is a general belief that the human-nature relationship is getting weaker over time, people are becoming more disconnected from nature over the decades. As there haven’t been regular and consistent measures over the years this can be difficult to evidence. We can infer a growing disconnection from cultural changes, such as the fall in use of nature words in books and films. Or simply the rise in damage done to the natural world, such as the 69% decline in wildlife populations since 1970. Handily, a paper published One Earth in February presents a global analysis of the changes in people’s psychological and physical connections to nature over time. This systematic review of over 70 articles and 100 case studies indicates that there has been a decline in human connection to nature over time. With this change varying by socio-economic and geographic settings. The work concludes that a better understanding of the human-nature relationship is crucial for a sustainable future. Such that researchers and policy makers should focus efforts on addressing this failing relationship.

A key aspect of work to address the human-nature relationship is that time in nature is different to nature connection. Time and visits are straightforward measures so get used in a great deal of research, but time and visits don’t necessarily indicate a close relationship. Several of my research papers and blog posts (e.g. here, here and here) cover the crucial difference between nature contact and nature connectedness. And a recent systematic review covering 832 independent studies provides an important summary on why the difference matters and the necessity to focus on psychological nature connection for a sustainable future. Some further work published in March adds to this.

A UK study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health also studies exposure to nature and connection with nature in tandem, therefore exploring how each explain wellbeing. After controlling for age and gender, the researchers found that greater nature connection significantly predicted lower depression and stress and improved well-being. Whereas the percentage of local green space did not significantly predict any mental health outcomes. There are many ways to measure green space and the quality and access to it matters. However, the work supports findings that indicate that nature connection is a significant component of the nature–health relationship – specifically that nature connection is linked with decreased depression, anxiety, stress and increased well-being.

Similarly, a US study published in People and Nature in February found more evidence on the benefit of nature connectedness for mental health and the need to move beyond access and excursions into nature towards engagement with nearby nature. The findings showed that nature connectedness was associated with less loneliness and greater mental health, but different types of nature engagement brought different results. In line with a previous work on simply noticing nearby nature, it was engagement with nearby nature that was linked with better mental health. While nature excursions such as camping and backpacking were linked to worse mental health. Similarly, media-based nature engagement wasn’t linked to positive benefits.

It is clear that engagement with nature, rather than simple provision of green space, is important to deliver the greatest benefits – especially the benefits important for a sustainable future. Those being increasing both human wellbeing and nature’s wellbeing through pro-nature behaviours. Supporting previous systematic reviews that have found a robust and causal link, a study published in March on pro-environmental behaviours across five countries found that a closer relationship to nature was linked to greater pro-environmental behaviour. However, further work published in Conservation Letters in March showed that priority actions for urban biodiversity conservation identified in the research, such as designing for human–nature connection, are yet to become mainstream in practice.

As the research supporting the importance of nature connectedness for a wellbeing and sustainable future increases, there is a need to understand nature connection, particularly in an urban context. Here, more recent work, again published in March, this time in Biological Conservation, explored the differences in nature connection across an urban population. Worryingly for a sustainable future, they found that it was students that exhibited the lowest nature connection. Importantly, amongst their findings was that less connected people stated that simply providing greater access to nature would not increase the nature engagement we’ve seen is crucial for building the close relationship that brings improved wellbeing and pro-nature behaviours.

The urban context is studied further in a paper published in Urban Forestry and Urban Greening in March. This study of urban green space use in Sweden found that nature connectedness was a key factor in green space use. With those people with weaker nature-connectedness more likely to perceive constraints such as danger from pests and therefore not wanting to visit green space. Conversely, those with greater nature connectedness perceived fewer constraints but wanted closer, higher quality and more peaceful green space.

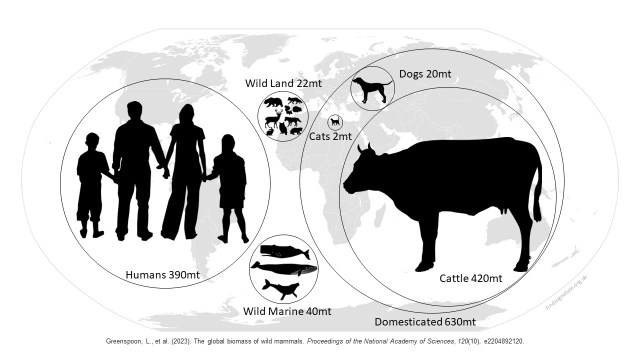

Finally, February saw the publication of further research in PNAS that reminds us of the failing human-nature relationship. This work quantified the biomass of wild mammals in comparison to the mass of humanity and its livestock. The work helps dispel notions about the endless ubiquity of wildlife and provides a compelling argument for the urgency of nature conservation efforts – and a new relationship with nature.

The research above is a small sample of nature connectedness work published in the past month or so. It reflects an increasing interest from nature conservation journals, showing that the need to focus on a new relationship with nature for a sustainable future is being understood by more people, more widely. However, many still don’t see that relationship as a tangible target for change, perhaps unaware of the mounting evidence. There is though a discernible shift in science-policy thinking, going far beyond treating the symptoms of a failing relationship to seeing that improving the human-nature relationship as a tangible solution.

Soga, M., & Gaston, K. J. (2023). Global synthesis reveals heterogeneous changes in connection of humans to nature. One Earth, 6(2), 131-138.

Wicks, C. L., Barton, J. L., Andrews, L., Orbell, S., Sandercock, G., & Wood, C. J. (2023). The Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Contribution of Local Green Space and Nature Connection to Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5083.

Phillips, T. B., Wells, N. M., Brown, A. H., Tralins, J. R., & Bonter, D. N. (2023). Nature and well‐being: The association of nature engagement and well‐being during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. People and Nature.

Soanes, K., Taylor, L., Ramalho, C. E., Maller, C., Parris, K., Bush, J., … & Threlfall, C. G. (2023). Conserving urban biodiversity: Current practice, barriers, and enablers. Conservation Letters, e12946.

Iwińska, K., Bieliński, J., Calheiros, C. S. C., Koutsouris, A., Kraszewska, M., & Mikusiński, G. (2023). The primary drivers of private-sphere pro-environmental behaviour in five European countries during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Cleaner Production, 393, 136330.

Selinske, M. J., Harrison, L., & Simmons, B. A. (2023). Examining connection to nature at multiple scales provides insights for urban conservation. Biological Conservation, 280, 109984.

Dawson, L., Elbakidze, M., van Ermel, L. K., Olsson, U., Ongena, Y. P., Schaffer, C., & Johansson, K. E. (2023). Why don’t we go outside?–Perceived constraints for users of urban greenspace in Sweden. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 82, 127865.

Greenspoon, L., Krieger, E., Sender, R., Rosenberg, Y., Bar-On, Y. M., Moran, U., … & Milo, R. (2023). The global biomass of wild mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(10), e2204892120.