A sustainable future requires more pro-environmental and pro-nature conservation action. Increasingly it is being recognised that fixing the human-nature relationship is an important factor in motivating positive behaviours towards the natural world. As we’ve shown in our recent paper, relationships and behaviour are linked. Nature connectedness captures the human-nature relationship, and it is known through systematic reviews that closer nature connection is linked to more sustainable behaviours. However, often nature connection is conflated with visits and access to nature. With the nature connection evidence sometimes used to suggest increased nature visits and access will lead to pro-nature action and a more sustainable future. Sadly, it’s not that simple.

Firstly, nature exposure doesn’t necessarily lead to increased nature connection as is seen in this study comparing planned nature connection activities to a walk in nature control. While nature visits have led to short-term increases in nature connection, sustained increases are rarely tested and when they are tend to be observed after regular nature activities and nature-noticing practices, or regular mindfulness and meditation practices. Also, nature connection aside, while visits and time in nature have been linked to pro-environmental behaviours, as we will see below, when connection is added to the mix it tends to matter more.

Clearly, equitable access to nature is hugely important. Even passive exposure to nature with little engagement is good for human health. All the better if that nature is rich in wildlife. That is a straightforward argument but approaches to access and visits need to be based on wider evidence. Increasing opportunity to access nature doesn’t necessarily increase orientation to engage with nature. Indeed, research has shown that nature orientation is the most significant factor in the use of green space, ahead of perceived accessibility.

Availability and ease of access to green space has tended to be the focus on the basis that greater opportunities will lead to increased use. However, when both opportunity and orientation are considered in tandem, orientation has been found to be a stronger factor in use, even when green spaces are as close as 250 meters. Once again nature orientation is the primary effect with researchers concluding ‘that measures to increase people’s connection to nature could be more important than measures to increase urban green space availability if we want to encourage park visitation’ – so to increase visits there is a need to consider connection.

Returning to the environmental crises, ultimately human wellbeing is dependent upon nature’s wellbeing. There is a need to ensure greater pro-nature behaviour and pursue the most effective ways to do that. Similarly, to wellbeing, previous research has tended to look at the links between nature access/visits and pro-environmental behaviour. Access, visits and time are relatively straightforward measures that are seen to be objective, but ‘describing things by certain characteristics rather than others merely because those characteristics are countable is a profoundly subjective decision’. Measures of access and visits will likely capture aspects of opportunity, orientation and connection, but recommendations tend to follow the metric and, therefore, focus on visits and access.

So, let’s look at the links between nature visits, connection, local access and pro-environmental behaviours. When measures related to orientation and connection are included results start to vary. For example, Alcock and colleagues found that an increase in nature visits led to an increase in general environmental behaviour, but about 2.5 times less than that predicted by nature appreciation.

When nature connectedness is introduced, things change again – plus an important distinction between pro-environmental (broadly carbon/resource use) and pro-nature conservation (broadly habitat related) behaviours emerges. Martin and colleagues found that nature visits were related to pro-environmental, but not pro-nature conservation behaviours. With the explanation of pro-environmental behaviours being almost twice as strong for nature connectedness. With nature connectedness also explaining pro-nature conservation behaviours, whereas visits did not. Local greenspace was unrelated to either behaviour. This work also found a strong relationship between nature connectedness and feeling one’s life is worthwhile (eudaemonic wellbeing), whereas nature visits were linked to general health.

Similarly, when focussing on pro-nature conservation behaviours, we found that it was nature connectedness and actively tuning into and noticing nature that best explained behaviour. With time in nature, knowledge/study of nature and value/concern for nature being non-significant. However, in real life factors tend not to work in isolation. We then find nature access and connection work together, meaning ‘access to do what?’ should always be considered.

In some recent and on-going work, we’ve been considering such factors again, namely how local greenspace, visits, connection and noticing explain pro-nature, pro-environmental behaviours and wellbeing. The complex statistical analysis is on-going, but in simple scrutiny of our data we’re finding that local green space (within 1km of a person’s home) has a very weak relationship to wellbeing (0.05), pro-environmental (0.05) and pro-nature behaviours (0.07). Nature visits have a weak relationship to eudemonic aspects of wellbeing (0.16), pro-environmental (0.13) and pro-nature behaviours (0.23). Nature connection has a moderate to strong relationship to wellbeing (0.30), pro-environmental (0.59) and pro-nature behaviours (0.64). With everyday noticing of nature having a similar relationship to wellbeing (0.24), pro-environmental (0.41) and pro-nature behaviours (0.56). Nature connection has a 2.5 to 4 times stronger relationship than visits on the pro-nature and pro-environmental behaviours. There’s much more work to be done on the direct and in-direct effects, but that is the start of the story.

Broadly, visits and time in nature (which are driven by orientation more than opportunity) are good for health and aspects of wellbeing, but less of a route to pro-environmental behaviours. Noticing and a close connection with nature are more strongly associated with different aspects of wellbeing, but also pro-nature and environmental behaviours – thereby doing more to unite both human and nature’s wellbeing for a sustainable future.

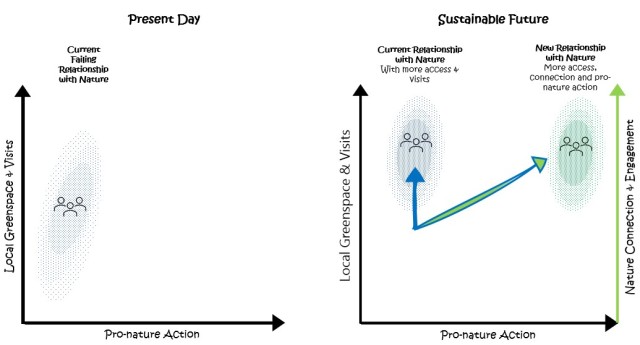

The indicative chart below attempts to capture this story. At present access to local greenspace and visits varies between communities more than it should, represented by the spread of blue dots. Efforts are underway to give more people access and tighten and raise that distribution, represented by the blue arrow below. This will contribute a certain amount to health and wellbeing of people. However, at a time of environmental crises there is also a need to deliver greater pro-nature behaviours through increased connection – the green & blue arrow. More access, visits and a closer connection with nature for wellbeing and pro-nature action represents a new relationship with nature. It’s worth considering whether nature engagement initiatives are heading down the blue or the blue & green arrow.

When such evidence is considered, it’s likely that a singular focus on access and visits will deliver more for people than it does for nature – and not as much for people as it could. For a sustainable future there is a need to consider both people and nature together. More broadly, thinking of the calls for a new relationship with nature, there’s a need to be careful that efforts, although very well intentioned, are not expanding our current failing relationship with nature – more of the same isn’t a new relationship. The chart above is closer to the reality in suggesting that most, perhaps all of us as a society, need to change – to move from blue to green.

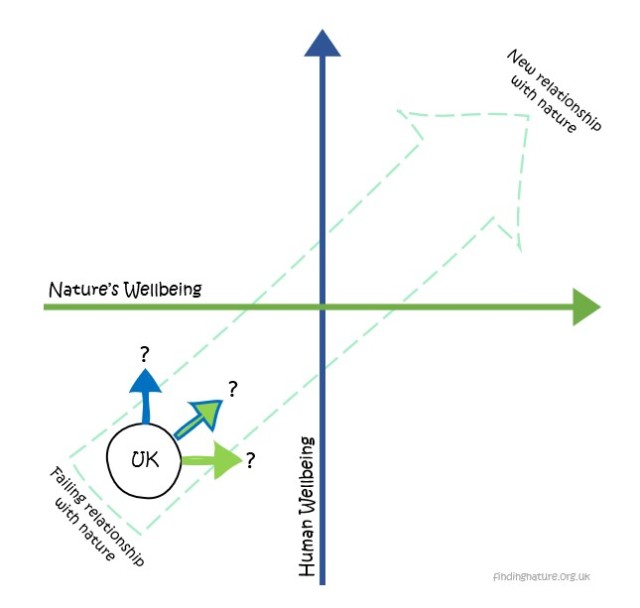

The second indicative chart tells a similar story. It is informed by a multinational survey published in Scientific Reports that included human wellbeing and wider biodiversity data (nature’s wellbeing). The survey showed that the UK was amongst the lowest nations for wellbeing (17th of 18), but also for nature connectedness (16th of 18) and nature visits (17th of 18). Separate data shows the UK is amongst the lowest for biodiversity, both of the 18, and globally. So, in the chart below it’s fair to place the UK in the bottom left quadrant – relatively low wellbeing for both humans and nature. As considered above, and the Scientific Reports paper concludes, the “Results also offer support for initiatives … aimed at increasing levels of psychological connectedness to the natural world, irrespective of direct exposure, for mental health as well as ecological reasons”. Once again, it’s important to ask if initiatives are heading down the blue arrow or the green & blue arrow towards a new relationship that unites both human and nature’s wellbeing.

Living in one of the most nature depleted countries on the planet and with a one of the weakest relationships with nature in Europe there’s a need to realise that our failing relationship with nature is deeply embedded. Looking back a few generations offers few solutions. When thinking about this, it is interesting to reflect on how older generations had a greater ‘home range’ – across generations children have had decreasing experiences of outdoor spaces (that have also become less biodiverse). Yet those older generations who played outside in more biodiverse times have witnessed and overseen the decline in biodiversity. It doesn’t offer a relationship to return to.

Within a modern, technological society a new relationship with nature is just that, new – we have not lived in harmony with nature for a very long time. So, a new relationship with nature for a sustainable future is about opportunity, orientation, engagement and embeddedness in nature – which itself is about a mindset shaped by macro-factors such as land use, consumerism, education, biodiversity and technology. It is these systemic issues affecting the human-nature relationship that must be addressed.

Too often we focus on the individual level rather than on the system the individual exists within. Too often we focus on changing standards and policies within the system, rather than the deeper leverage points such as goals, institutions, and structures. And too often we focus on one side, be it people or nature, rather than the relationship between the two – and acting on the basis that they are one and the same. Through nurturing this worldview and realising our place within nature, it is possible to unite both human and the rest of nature’s wellbeing.