Joint blog with Dr Mike Lengieza from Durham University

Major environmental institutions around the globe are realising that the failing human-nature relationship with nature is a root cause of environmental issues. Yet, designing for human–nature connection is yet to become mainstream in practice. Although there have been successful interventions and frameworks such as the pathways to nature connectedness, more can be done to facilitate targeting the human-nature relationship in policy. First by establishing it as a target for change, then by drawing parallels between nature connectedness research and research on interpersonal relationships. This provides new routes to a closer human–nature relationship – and pro-environmental action. Our latest paper published in Sustainability reviews recent references to the human–nature relationship in policy documents and then draws on theories of interpersonal relationships to illustrate how they can inform efforts to repair the human–nature relationship for a more sustainable future.

Like elsewhere in life a close & sustainable relationship with nature should be built on intimacy, commitment, interdependence, reciprocity and trust.

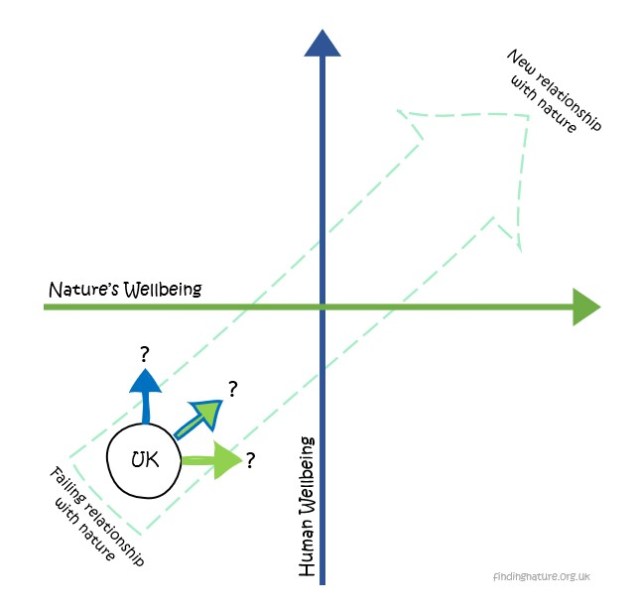

Few would deny the existence of relationships between people, that some are close, others more distant. And that these interpersonal relationships motivate behaviour. Yet, many overlook the human-nature relationship, focussing instead on the tangible symptoms of that failing relationship: biodiversity loss and climate warming without considering the underlying problem. For current sustainability efforts to be successful there is also a need to reverse our growing disconnection from the rest of nature.

Human-nature Relationships in Policy

Thankfully, in recent times, major environmental institutions are recognising this and have been advocating for a profound shift in our relationship with nature. The UN Environmental Programme’s report, “Making Peace with Nature,” proposes that we must change our values and mindsets, moving away from material consumption and recognizing nature’s integral role in a good life. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted at COP15, acknowledges the exploitation of nature driven by societal values and behaviours as the root cause of biodiversity loss. It emphasizes living in harmony with nature and includes nature connection as a target.

The push for greater specificity in policy has seen references to “nature connectedness” research in various documents. Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future underscores the need to redefine our relationship with nature, shifting from extraction to care. The EEA briefing, ‘Exiting the Anthropocene? Exploring fundamental change in our relationship with nature,’ delves into the deep interconnection between humans and ecosystems for a sustainable future.

Similarly, the Dasgupta Review commissioned by the UK Government delves into the spiritual and sacred aspects of the human-nature relationship. It highlights the distinction between mere contact with nature and true connectedness, emphasizing that the latter goes beyond personal well-being to motivate environmental behaviour.

While there has been progress in recognizing the importance of our connection to nature in policy, the challenge lies in operationalising it fully. One key area of concern is the lack of specificity in policy language. Many policies use ambiguous terms, leaving the emphasis on the human-nature relationship implicit or vague. To address this, the psychological construct of “nature connectedness” should be used more widely as a focal point for targeted and effective policy actions. While there is progress in acknowledging the benefits of nature connectedness for both human health and nature conservation, it is yet to become mainstream in practice.

Another issue lies in the sufficiency of policy aims. While some policies claim to address the human-nature relationship, they often focus on outcomes that fall short of genuinely influencing the relationship. Merely promoting access to nature, while essential, is not enough to increase nature connectedness – in the terms of interpersonal relationships, having access to the room doesn’t mean you’ll develop a close relationship with those inside.

To successfully target the human-nature relationship in policies, there must be explicit recognition that the human–nature relationship is a relationship and that it must be a clear and explicit target. Policy language must also be more precise. In the paper we argue that the human-nature relationship is as real as any interpersonal relationship and policymakers should draw from wider theories on interpersonal relationships to operationalize the human-nature relationship effectively; specifically, it can be easily operationalized as nature connectedness. By addressing these areas of weakness, environmental policy can play a more significant role in nurturing a harmonious and sustainable relationship with nature.

Interpersonal Relationships

Relationships play a fundamental role in shaping our lives, fulfilling our needs for self-expansion and belonging. By including others in our sense of self, we enhance our resources and well-being. These vital connections affect not only our psychological wellbeing and identity but also influence how we treat others and engage in pro-social behaviours. Close relationships, where we prioritize the interests of our partners and the relationship itself over self-interest, lead to greater willingness to sacrifice and accommodate during conflicts. Fostering stronger interpersonal bonds benefits both individuals and society, creating a more caring and supportive community.

The significance of interpersonal relationships in our lives has led to extensive research on factors influencing closeness and commitment. While spending time together is crucial, the quality of interaction plays a pivotal role in relationship development. Self-disclosure fosters intimacy, and engaging in novel activities strengthens closeness. Mutual influence, or interdependence, contributes to a lasting, committed relationship. Commitment stems from investing time and resources, fulfilling crucial needs, and lacking attractive alternatives.

In human-nature relationships, the importance of going beyond mere contact becomes evident. Discussions often revolve around facilitating contact with nature, but the principles of interpersonal relationships show that true connection requires more. Intimacy, excitement, and interdependence are vital ingredients for nurturing meaningful bonds. Emphasising these aspects can provide valuable insights for fostering a deeper and more committed relationship with nature.

Parallels between Interpersonal Relationships and Human–Nature Relationships

The concept of relationship closeness, where we include others in our sense of self, also extends to our relationship with nature, known as nature connectedness. This implies that our bond with nature can be seen as just another form of relationship. Interestingly, nature connectedness and interpersonal relationships share many parallels in their associations with important outcomes – a summary of key concepts and their parallels to human–nature relationships can be found in Table 1 of the paper.

Nature connectedness fulfils our need for relatedness and expands our sense of self. It is linked to well-being, behaviour, and prosocial actions. Furthermore, nature connectedness is deeply intertwined with our sense of identity, showcasing its similarities to interpersonal relationships.

Considering the similarities between nature connectedness and interpersonal relationships, it’s reasonable to believe they might have similar determinants. Treating nature connectedness as a type of relationship can offer a fresh perspective on our disconnect with nature; if one recognizes that nature connectedness is a relationship, it becomes obvious that merely promoting contact with nature is necessary, but wholly insufficient to repair our relationship with nature. By applying principles from interpersonal relationships to nature connectedness, we can uncover new insights, identify areas for further research, and make meaningful implications for policy and practice.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The research suggests that human-nature relationships share some striking similarities with our close relationships with other people. Just as we seek emotional intimacy and a sense of interdependence with our loved ones, these elements also play a crucial role in fostering a deep bond with nature. But here’s the thing—while we know that spending time in nature is beneficial, it’s not just about mere contact. We may spend hours together in the workplace, but that doesn’t guarantee a close relationship. Like in interpersonal relationships, the quality of our interaction with nature matters too.

Imagine walking barefoot through the grass, experiencing the joy of planting a tree and seeing it begin to grow, or visiting your favourite nature spot, like you would a long time friend. These acts of intimacy and meaningful interdependence with nature can have a profound impact on our nature connectedness. Similarly, the way we learn about nature is important. Environmental education should move beyond textbook knowledge and focus on exciting activities that create a personal connection with nature. Moreover, our cultural and societal norms heavily influence how we view and interact with nature. The history of Western society reveals a complex relationship with nature, often dominated by use and control. This societal relationship must be re-evaluated.

We should recognise that different types of relationships exist, and it’s no different for our bond with nature. Some relationships are self-centric, driven by personal gain, while others are ‘ecosystemic’, emphasizing mutual concern and wellbeing. Encouraging ecosystemic relationships with nature is crucial for positive treatment of the environment.

Like any relationship, trust plays a pivotal role in our connection with nature. Trusting that nature will be benevolent and responsive is vital for forming a strong bond. However, trust in nature is often understudied, especially in childhood. It’s essential to nurture this trust early on, and societal attitudes can influence how we perceive nature’s reliability.

As we navigate the complexities of our modern lives, we must recognize the barriers that hinder our human-nature relationship. Stress, societal norms, and alternative ways to fulfil our needs can all interfere with fostering a deep and authentic connection with nature. It’s vital to confront these obstacles and identify ways to overcome them.

In essence, understanding the similarities between interpersonal relationships and human-nature relationships can transform the way we approach our connection with nature. By building trust, promoting intimacy, and diversifying our interactions with nature, we can foster a more profound and lasting bond. A summary of specific policy recommendations can be found in Table 2 of the paper.

The Trusting and Reciprocal Relationship Challenge

Through the fascinating connection between human-nature relationships and interpersonal relationships, we encounter some thought-provoking challenges. While trust plays a vital role in both types of relationships, trust in nature may not adhere to the same principles as trust in people. Nature’s behaviour can be less predictable, making it challenging to perceive its reliability and intrinsic benevolence. Many may even perceive nature as a nuisance or at times dangerous.

Additionally, interpersonal relationships involve reciprocity, with both parties contributing to the relationship’s development. However, human-nature relationships are often perceived as one-sided, with nature being seen as inanimate and non-reciprocal. Bridging this gap requires recognising the concept of animacy, where nature is viewed as autonomous and communicative, and comprised by relational beings. Embracing this animistic philosophy may help foster a deeper sense of reciprocity in our connection with nature. This requires a larger cultural shift away from the Western worldview that perceives nature as a mere resource to be used and controlled. Embracing diverse worldviews and incorporating relational nature education could be essential steps toward nurturing a more meaningful and reciprocal relationship with nature.

Conclusion

This review reminds us of the profound impact relationships have on our lives, not just with other people but also with nature. Understanding the parallels between interpersonal relationships and nature connectedness sheds light on the importance of nurturing our bond with the natural world. This connection is essential, not only for our own well-being but also for the well-being of the planet.

To mend our broken relationship with nature, we need a cultural shift. Our modern world, driven by scientific and industrial revolutions, has disconnected us from nature, viewing it as a resource to be used and controlled. However, hope lies in recognising that past cultural shifts have occurred, and we can envision a more sustainable future where human-nature relationships are valued.

This vision must be supported by meaningful actions and policies. Environmental policy should acknowledge the tangible impact of relationships and guide urban planning to create spaces for shared care of nature. Cultural policy and incentives can foster exciting engagement with nature, while education and health policies can promote animistic thinking essential for healthy relationships with nature. Furthermore, legal frameworks can grant nature rights and personhood, legitimizing it as a valued member of our planetary community. By embracing a relationship-focused approach, we can pave the way for a sustainable future where humanity and nature thrive in harmony.

Lengieza ML, Aviste R, Richardson M. The Human–Nature Relationship as a Tangible Target for Pro-Environmental Behaviour—Guidance from Interpersonal Relationships. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612175