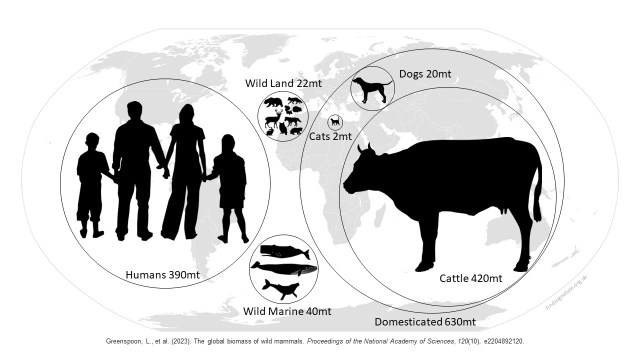

Spring is a time of new relationships, between parents and their young, as new growth emerges from old. Spring also sees anniversaries for two environmentalists who emphasized people’s relationships with nature. John Muir, born April 1838, shaped people’s appreciation for wild nature. Rachel Carson, who died April 1964, highlighted the dangers of pesticides in Silent Spring, one example of a controlling relationship with nature. Despite their work, and the efforts of countless others, over two-thirds of wildlife populations have been lost since 1970 [1]. Spring has grown quieter.

Spring is a time of new relationships, but only a new relationship with nature can prevent a silent spring.

Since the early 1990s, no country has met the basic needs of its population without overconsuming natural resources [2]. The destruction of habitats and wildlife, together with climate change, show that the human-nature relationship is broken. It is dominated by use and control.

People in countries like the US and Britain have some of the weakest relationships with nature [3]. Nations that have had particularly fast levels of growth and consumption since Muir’s birth. This growth, fuelled by the use and control of natural resources, has improved our lives in innumerable ways, but at a devasting cost to the environment and our bond with nature. Over time, the language used in the books, films and songs that reflect our preoccupations and tastes refers to nature less and less [4]. Instead, we increasingly celebrate ourselves. The use of the word ‘me’ has increased four-fold since 1990 [5]. It is being human, rather than of nature, that brings meaning to our lives. People are increasingly self-interested, and we focus on using our technology to ‘fix’ the symptoms of the broken relationship, such as targeting zero carbon.

The relationship with nature that is the root cause of the environmental crises is rarely seen as a tangible target for change. Yet it is that relationship that drives our behaviour towards the natural world [6]. Corporations have used the emotions and meaning that form relationships to drive consumer behaviour for decades [7]. The consumer world is also a battle for attention between brands, products and experiences, but nature doesn’t have an advertising budget. Yet it is noticing nature, the joy and meaning that it brings, that builds the close relationship that brings pro-nature behaviours [8]. Too often in our consumer world, nature is simply a resource for recreation, an opportunity for a selfie where we can celebrate ourselves.

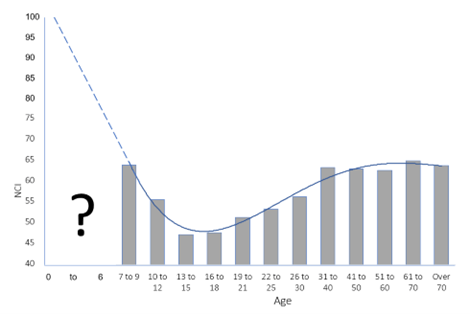

Our efforts to form a relationship with nature are often misguided. Outdoor adventure, enjoyed by Muir, is often assumed to improve people’s bond with nature but has been found not to [9]. Excursions such as hiking have been found to have limited benefits when compared to simpler engagement with nearby nature [10]. Similarly, environmental education does not tend to increase nature connection and pro-nature behaviours [11]. Facts and figures don’t form relationships, they can strip nature of its joy and meaning.

The division of nature to understand hides surprising and real connections that are the basis of life. Our microbiome – the myriad of microorganisms that live on and inside us – plays a vital role in our wellbeing. Each of us is a community of half human and half microbial cells in a symbiotic relationship [12]. Our bodies have an innate and unseen union with the rest of nature, such that simply viewing flowers or touching oak can be detected in physiological changes that help manage our emotions [13]. Controlled, dissected, exploited, and ignored, nature disappears from our landscapes, our lives and Spring.

Unseen connections re-emerge in Spring and relationships can be rekindled. This can begin without excursions, simply by noticing nature close to home, finding wilderness in an individual flower. A simple act that repeated can build a relationship with nature that brings sustained benefits to mental wellbeing and feelings of living a worthwhile life [14]. A relationship that unites both human and nature’s wellbeing. A society that celebrates and realises its place within nature will prevent a silent spring – a positive vision, not just a future denied the use and control of nature’s resources.

[1] WWF (2022). Living Planet Report, https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-GB/

[2] Fanning, A. L., O’Neill, D. W., Hickel, J., & Roux, N. (2021). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nature Sustainability, 1–11; https://sustainabilitycommunity.springernature.com/posts/draft

[3] White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., Grellier, J., et al. (2021). Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries. Scientific Reports, 11, 8903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87675-0

[4] Kesebir, S., & Kesebir, P. (2017). A growing disconnection from nature is evident in cultural products. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 258–69.

[5] Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Gentile, B. (2013). Changes in pronoun use in American books and the rise of individualism, 1960–2008. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(3), 406–15; Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Gentile, B. (2012). Increases in individualistic words and phrases in American books, 1960–2008. PloS One, 7(7), e40181; Richardson, M. (2022,). Me, myself and nature. Finding Nature. https://findingnature.org.uk/2022/08/31/nature-versus-me/

[6] Mackay, C. M., & Schmitt, M. T. (2019). Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101323. Whitburn, J., Linklater, W., & Abrahamse, W. (2020). Meta‐analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conservation Biology, 34(1), 180–93.

[7] Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–40.

[8] Sheffield, D., Butler, C. W., & Richardson, M. (2022). Improving Nature Connectedness in Adults: A Meta-Analysis, Review and Agenda. Sustainability, 14(19), 12494; Richardson, M., Hamlin, I., Butler, C. W., et al. (2021). Actively noticing nature (not just time in nature) helps promote nature connectedness. Ecopsychology. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2021.0023; Richardson, M., Passmore, H. A., Barbett, L., et al. (2020). The green care code: how nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro‐nature conservation behaviours. People and Nature, 2(3), 821–39.

[9] Williams, I. R., Rose, L. M., Raniti, M. B., et al. (2018). The impact of an outdoor adventure program on positive adolescent development: a controlled crossover trial. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(2), 207–36.

[10] Phillips, T. B., Wells, N. M., Brown, A. H., Tralins, J. R., & Bonter, D. N. (2023). Nature and well‐being: The association of nature engagement and well‐being during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. People and Nature.

[11] Otto, S., & Pensini, P. (2017). Nature-based environmental education of children: environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Global Environmental Change, 47, 88–94; Barragan-Jason, G., de Mazancourt, C., Parmesan, C., et al. (2021). Human–nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: a global meta-analysis. Conservation Letters, e1285.

[12] Robinson, J. M., Mills, J. G., & Breed, M. F. (2018). Walking ecosystems in microbiome-inspired green infrastructure: an ecological perspective on enhancing personal and planetary health. Challenges, 9(2), 40; Sender, R., Fuchs, S., & Milo, R. (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biology, 14(8), e1002533.

[13] Ikei, H., Song, C., & Miyazaki, Y. (2017). Physiological effects of touching wood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 801; Lee, J., Park, B. J., Tsunetsugu, Y., et al. (2011). Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health, 125(2), 93–100.

[14] Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: a meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(3), 1145–67; Martin, L., White, M. P., Hunt, A., et al. (2020). Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68, 101389.McEwan, K., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., et al. (2019). A smartphone app for improving mental health through connecting with urban nature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3373.