The Nature Connectedness Research Group is 10 years old! I set it up in May 2013. It seemed intuitive to me that the human relationship with nature mattered and was at the heart of environmental crises. Looking back to 2013 I founded it to ‘understand people’s connection to the natural environment and design and evaluate local interventions in order to improve connectedness; bringing about the associated benefits in well-being and conservation behaviour’ – it’s gone well! The group has produced a large amount of research, applied it widely and been recognised for its work – winning two Green Gown Research with Impact awards in 2021 and being named by Universities UK as one of the UK’s 100 best breakthroughs for its impact.

With increased recognition of the human-nature relationship being a root cause of the environmental crises, the Nature Connectedness Research Group is doing what it can to lead efforts to create a new relationship with nature, through research to understand, application through frameworks and interventions and sharing guidance.

Our Research

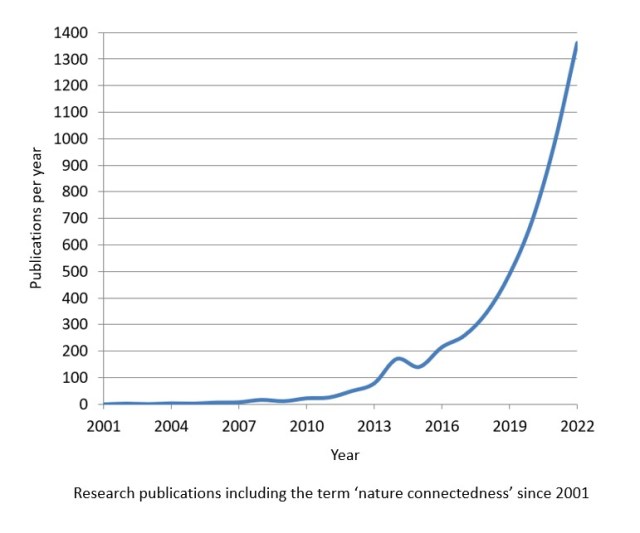

Clearly, a research group starts with research. The Nature Connectedness Research Group was perhaps the first to focus squarely in this area. In 2013 only a few research papers used the term ‘nature connectedness’ in their title with 77 using the term at all. By 2022 that 77 had grown to 1410.

The research projects have ranged from small student projects, those done on a shoestring (or zero!) budget to two large scale £1+ million consortium programmes – Improving Wellbeing through Urban Nature (2016 to 2019) and Connected Treescapes (2021 to present).

The projects have produced a lot of research findings. I’m unsure how many now, but in that time getting on for 100 journal papers involving over 20 University of Derby staff have been published – there’s a list of some below. They can be split into a few areas of focus.

Environmental Factors: The group has examined the influence of environmental factors on nature connectedness. From investigating the impact of avian biodiversity in urban green spaces on human emotions to exploring the association between visible garden biodiversity and nature connectedness, the group has highlighted the significance of nature’s diversity in shaping human well-being.

Mental Well-being and Health: Researchers have explored the links between nature connectedness and various aspects of well-being, including eudaimonic well-being, mood, and mental health. Investigations into the effects of forest-bathing, mindfulness-based interventions, nature writing tasks, and nature-based positive psychological interventions have demonstrated the potential of nature connection approaches to enhance mental well-being and promote emotion regulation. We have explored green prescriptions and nature connectedness approaches for populations including those living with addiction, psychopathy, paranoia, disordered eating, and anxiety.

Psychological Dimensions: Such as the relationship between nature connectedness, nonattachment, and engagement with nature’s beauty has revealed how individuals can derive meaning and fulfilment from their connection to the natural world. The group has investigated the connection between nature connectedness and dark personality traits, unravelling the complex interplay between individual traits and environmental attitudes.

Measurement: Another area of focus has been developing measures (e.g. the NCI and ProCoBs) so that researchers can better understand the factors that drive individuals to engage in sustainable practices. Furthermore, the group has examined the influence of nature connectedness on parental self-efficacy, highlighting the role of caregivers in fostering nature connection in their children. Our work has suggested that nature connectedness is a key metric for sustainable future.

Interventions and Engagement: Understanding how to effectively connect people with nature has been a core focus of the group’s research. Through evaluating interventions such as green outdoor educational programs and outdoor, arts-based activities, the researchers have identified strategies to foster nature connectedness. Additionally, the exploration of the impact of the “30 days wild” campaign has shed light on the potential of large-scale initiatives to enhance nature connectedness and well-being.

Details of much of this work can be found by searching this site.

Our Impact

As a former engineer with a focus on human factors (the fit between people and the things they do) solutions are important to me. And the research above has been applied wherever possible. It falls into three themes.

Improving the human-nature relationship through via the pathways to nature connectedness.

Our pathways to nature connectedness design framework has been widely adopted by organisations in the UK and around the world to help connect people with nature. We have worked with a range of partners, including Natural England, National Trust, and the Wildlife Trusts and other environmental NGOs and organisations of all shapes and sizes across public, charitable, and private sectors. Our research and knowledge exchange work is broad in scope, contributing to the visitor experience and engagement at nature reserves, activities within green social prescribing and mental wellness programmes, policy briefings, design of buildings and landscapes, artworks, leadership development, and educational programmes. Case studies on the ‘Pathways to Nature Connectedness’ from the organisations above and others such as Plymouth City Council can be found in our Nature Connection Handbook.

The pathways also inform the Government’s Green Influencers scheme and the Green Recovery Challenge Fund guidance thereby informing initiatives such as Generation Green where organisations such as the YHA, Scouts, National Parks connect young people with nature. In 2015, the Wildlife Trusts used the pathways to inform the design of their innovative ‘30 Days Wild’ national programme with over one million people taking part in the first 5 years. In 2018, the National Trust adopted the pathways as a framework they could apply to the design of visitor experience activities and programmes. One part of this work was a refresh of the national campaign “50 things to do before you’re 11¾” which was launched nationally in Easter 2019. The pathways have also informed physical spaces, for example the Butterfly House at Durrell Zoo and Silence at Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

The utility of the pathways framework for application across contexts to improve human-nature relations – from design of local programmes to policy and urban places has been included in policy briefings and evidence reviews such as Stockholm+50, a UN science evidence review. For more transformative change, we are developing the use of the pathways to inform urban design and to inform policy and culture through the use of system leverage points for transformational change.

Nature connection for mental health and wellbeing

Our nature connection focussed interventions have led to clinically significant improvements in mental health, with the research informing policy briefings, green social prescription schemes and the Mental Health Foundation’s 2021 Mental Health Awareness Week – the world’s largest mental health week campaign. Our ‘three good things in nature’ approach has part of a green prescription pilot run by RSPB Scotland. Our research also informs the work of Mind, again see our Nature Connection Handbook.

Nature connection and pro-nature behaviour measures.

We were part of the team that developed the Nature Connection Index (NCI) a measure designed to be suitable for both children and adults in populations surveys. The NCI helped us to be among the first to identify the ‘teenage dip’ in nature connection.

We have also created the first scale to measure pro-nature conservation behaviours, the Pro-Nature Conservation Behaviour Scale – or ProCoBS for short. ProCoBS is a psychometrically validated scale measuring active behaviours that specifically support the conservation of biodiversity. ProCoBS has enabled us to do work that showed that being connected to nature plays a vital role in pro-nature conservation behaviours.

Both measures have been included in Natural England’s People & Nature Survey, enabling the impact of nature connection on wellbeing and pro-nature behaviours to be explored at population scale.

Biodiversity Stripes

More recently I’ve developed the biodiversity stripes. They were swiftly adopted by the Nature Positive campaign led by Nature4Climate. A global effort to raise the profile of action to protect, manage and restore natural ecosystems for the benefit of the world’s peoples, the climate and biodiversity. They appeared at the COP27 Nature Zone and alongside the climate warming stripes, the biodiversity stripes decorated a baton taken to COP15 to unite the climate and nature agenda. The stripes have featured in the French Parliament and national TV.

Global Bio Stripes 1970 to 2018 – Data: Living Planet Index http://stats.livingplanetindex.org/

Overall, over 20 of our research papers have been referenced 70 or so times in 46 documents from 28 policy bodies in 12 countries, including the IPCC, WHO, EU OECD, and Governments of New Zealand, Finland and the UK.

Where Next

Since forming, the Nature Connectedness Research Group has done a great deal to show nature connection can unite both human and nature’s wellbeing, but we are always looking forwards to more research, more application and sharing – with aim to make an even bigger difference to the human-nature relationship for a more sustainable future. These steps are much more challenging, but there is momentum.

A sustainable future requires a transformational change in our relationship with nature. Large-scale social and cultural shifts are needed to meet the challenges we face in addressing the climate and wildlife emergencies. Nature connectedness captures that relationship and the principles can be applied at a wider scale across the public realm to change how people relate to the rest of the natural world. With the focus of many sustainability initiatives being on reduction and restriction, nature connection offers a positive vision of a vibrant and nature-rich world that helps people feel good and live meaningful lives.

With others, the NCRG can hopefully find a way to shape the future of our institutions, spaces, and processes: putting nature connection into education’s curricula, teaching spaces or practices; designing landscapes, urban spaces, and buildings that provide for and prompt engagement with nature; creating technologies that connect rather than disconnect humans from nature; developing health and social care services that integrate nature connection; or inspiring families, friends and communities to come together to enjoy and nurture nature.

A selection of NCRG Publications

There have been dozens of journal papers involving approx. 20 UoD staff across a range of disciplines, here’s a selection:

Barbett, L., Stupple, E. J. N., Sweet, M., Schofield, M. B., & Richardson, M. (2020). Measuring Actions for Nature—Development and Validation of a Pro-Nature Conservation Behaviour Scale. Sustainability, 12(12), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124885

Barnes, C., Harvey, C., Holland, F., & Wall, S. (2021). Development and testing of the Nature Connectedness Parental Self-Efficacy (NCPSE) scale. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 65, 127343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127343

Barrows, P. D., Richardson, M., Hamlin, I., & Van Gordon, W. (2022). Nature Connectedness, Nonattachment, and Engagement with Nature’s Beauty Predict Pro-Nature Conservation Behavior. Ecopsychology, 14(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2021.0036

Cameron, R. W., Brindley, P., Mears, M., McEwan, K., Ferguson, F., Sheffield, D., … & Richardson, M. (2020). Where the wild things are! Do urban green spaces with greater avian biodiversity promote more positive emotions in humans?. Urban Ecosystems, 23(2), 301-317.

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2020). Does a natural environment enhance the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)? Examining the mental health and wellbeing, and nature connectedness benefits. Landscape and Urban Planning, 202, 103886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103886

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2020). Simulated natural environments bolster the effectiveness of a mindfulness programme: A comparison with a relaxation-based intervention. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 67, 101382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101382

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2021). Examining the effectiveness of mindfulness practice in simulated and actual natural environments: Secondary data analysis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 66, 127414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127414

Dobson, J., Birch, J., Brindley, P., Henneberry, J., McEwan, K., Mears, M., Richardson, M. & Jorgensen, A (2020). The magic of the mundane: The vulnerable web of connections between urban nature and wellbeing. Cities, 108, 102989.

Fido, D., Rees, A., Clarke, P., Petronzi, D., & Richardson, M. (2020). Examining the connection between nature connectedness and dark personality. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 101499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101499

Fido, D., & Richardson, M. (2019). Empathy mediates the relationship between nature connectedness and both callous and uncaring traits. Ecopsychology, 11(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0071

Garip, G., Rees, A. & Richardson, M. (2021). Development and implementation of evaluation resources for a green outdoor educational program. Journal of Environmental Education, 52(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2020.1845588

Hallam. J., Gallagher, L., & Harvey C. (2021) ‘I don’t wanna go. I’m staying. This is my home now.’ Analysis of an intervention for connecting young people to urban nature. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127341

Hallam J., Gallagher, L., & Harvey, C. (2019). ‘We’ve been exploring and adventuring.’ An investigation into young people’s engagement with a semi-wild, disused space. The Humanistic Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000158

Hallam, J., Gallagher, L., & Owen K. (2021). The secret language of flowers: insights from an outdoor, arts-based intervention designed to connect primary school children to locally accessible nature. Environmental Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1994926

Hamlin, I., & Richardson, M. (2022). Visible Garden Biodiversity Is Associated with Noticing Nature and Nature Connectedness. Ecopsychology, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2021.0064

Harvey, C., Sheffield, D., Richardson, M., & Wells, R. (2022). The Impact of a “Three Good Things in Nature” Writing Task on Nature Connectedness, Pro-nature Conservation Behavior, Life Satisfaction, and Mindfulness in Children. Ecopsychology. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2022.0014

Keenan, R., Lumber, R., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2021). Three good things in nature: A nature-based positive psychological intervention to improve mood and well-being for depression and anxiety. Journal of Public Mental Health, 20(4), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-02-2021-0029

Kotera, Y., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2020). Effects of shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy on mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00363-4

Lumber, R., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2017). Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186

Martin, L., White, M. P., Hunt, A., Richardson, M., Pahl, S., & Burt, J. (2020). Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101389

McEwan, K., Richardson, M., Brindley, P., Sheffield, D., Tait, C., Johnson, S., Sutch, H., & Ferguson, F. J. (2020). Shmapped: Development of an app to record and promote the well-being benefits of noticing urban nature. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(3), 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz027

McEwan, K., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., Ferguson, F. J., & Brindley, P. (2021). Assessing the feasibility of public engagement in a smartphone app to improve well-being through nature connection (Evaluación de la factibilidad de la implicación ciudadana mediante una app de teléfonos inteligentes para mejorar el bienestar a través de la conexión con la naturaleza). Psyecology, 12(1), 45-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/21711976.2020.1851878

McEwan, K., Giles, D., Clarke, F.J., Kotera, Y., Evans, G., Terebenina, O., Minou, L., Teeling, C. & Wood, W. (2021). A pragmatic controlled trial of Forest Bathing compared with Compassionate Mind Training in a UK population: impacts on self-reported wellbeing and heart rate variability. Sustainability

Muneghina, O., Van Gordon, W., Barrows, P., & Richardson, M. (2021). A novel mindful nature connectedness intervention improves paranoia but not anxiety in a nonclinical population. Ecopsychology, 13(4), 248-256. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2020.0068

Passmore, H.-A., Martin, L., Richardson, M., White, M., Hunt, A., & Pahl, S. (2021). Parental/Guardians’ connection to nature better predicts children’s nature connectedness than visits or area-level characteristics. Ecopsychology, 13(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2020.0033

Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 21(3), 1145–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6

Richardson, M. (2019). Beyond restoration: Considering emotion regulation in natural well-being. Ecopsychology, 11(2), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0012

Richardson, M., & Butler, C. W. (2022). Nature connectedness and biophilic design. Building Research & Information, 50(1–2), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2021.2006594

Richardson, J. Dobson, D. J. Abson, R. Lumber, A. Hunt, R. Young & B. Moorhouse (2020) Applying the pathways to nature connectedness at a societal scale: a leverage points perspective, Ecosystems and People, 16(1), 387-401.

Richardson, M., & Hamlin, I. (2021). Nature engagement for human and nature’s well-being during the Corona pandemic. Journal of Public Mental Health, 20(2), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-02-2021-0016

Richardson, M., Hamlin, I., Butler, C. W., Thomas, R., & Hunt, A. (2022). Actively noticing nature (not just time in nature) helps promote nature connectedness. Ecopsychology, 14(1), 8-16.

Richardson, M., Hamlin, I., Elliott, L. R., & White, M. P. (2022). Country-level factors in a failing relationship with nature: Nature connectedness as a key metric for a sustainable future. Ambio, 51(11), 2201–2213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01744-w

Richardson, M., Hunt, A., Hinds, J., Bragg, R., Fido, D., Petronzi, D., Barbett, L., Clitherow, T., & White, M. (2019). A Measure of Nature Connectedness for Children and Adults: Validation, Performance, and Insights. Sustainability, 11(12), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123250

Richardson, M., Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Problematic smartphone use, nature connectedness, and anxiety. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.10

Richardson, M., Maspero, M., Golightly, D., Sheffield, D., Staples, V., & Lumber, R. (2017). Nature: A new paradigm for well-being and ergonomics. Ergonomics, 60(2), 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2016.1157213

Richardson, M., & McEwan, K. (2018). 30 days wild and the relationships between engagement with nature’s beauty, nature connectedness and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01500

Richardson, M., McEwan, K., & Garip, G. (2018). 30 days wild: Who benefits most? Journal of Public Mental Health, 17(3), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-02-2018-0018

Richardson, M., Passmore, H.-A., Barbett, L., Lumber, R., Thomas, R., & Hunt, A. (2020). The green care code: How nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro-nature conservation behaviours. People and Nature, 2(3), 821–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10117

Richardson, M., Passmore, H.-A., Lumber, R., Thomas, R., & Hunt, A. (2021). Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship. International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v11i1.1267

Richardson, M., Richardson, E., Hallam, J., & Ferguson, F. J. (2020). Opening doors to nature: Bringing calm and raising aspirations of vulnerable young people through nature-based intervention. The Humanistic Psychologist, 48(3), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000148

Sheffield, D., Butler, C. W., & Richardson, M. (2022). Improving Nature Connectedness in Adults: A Meta-Analysis, Review and Agenda. Sustainability, 14(19), 12494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912494

Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Richardson, M. (2018). Mindfulness and nature. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1655–1658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0883-6