Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta led the review on the economics of biodiversity that was announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in March 2019. The review set out to assess the economic benefits of biodiversity and the costs and risks of biodiversity loss before identifying actions that can enhance biodiversity and economic prosperity. The review was published early in 2021, but at 610 pages it’s taken me a while to compile my thoughts. This blog considers the aspects most relevant to human-nature connectedness – of which there are many.

The Dasgupta Review recognises the essence of nature connectedness and it runs as a theme through relevant chapters. The review acknowledges the adoption of anthropocentric viewpoint – the value that nature provides to human wellbeing. This is discussed with reference to sacredness and the different systems of belief and thought that go beyond an anthropocentric perspective (section 1.8). Sacredness is discussed further, how it can include a sense of awe and wonder that we know contributes to nature connectedness and human wellbeing.

The Dasgupta Review goes beyond the essence of nature connectedness, to discussing it directly. The review notes the ‘admirable’ 2015 review of the wellbeing benefits of nature connectedness by Capaldi and colleagues (we published a review more recently). The Dasgupta Review accepts the distinction between contact with nature and connectedness with nature. When discussing contact and connection, it’s interesting that the review notes that:

“Psychologists would appear to be on firmer ground when reporting the role contact with Nature plays in our sense of well-being. The influence on our well-being of connectedness with Nature is less assured empirically, at least as of now. The reason may be that connectedness is more difficult to achieve than making contact with the natural world. So, most studies have looked for the influence of contact on hedonic well-being.”

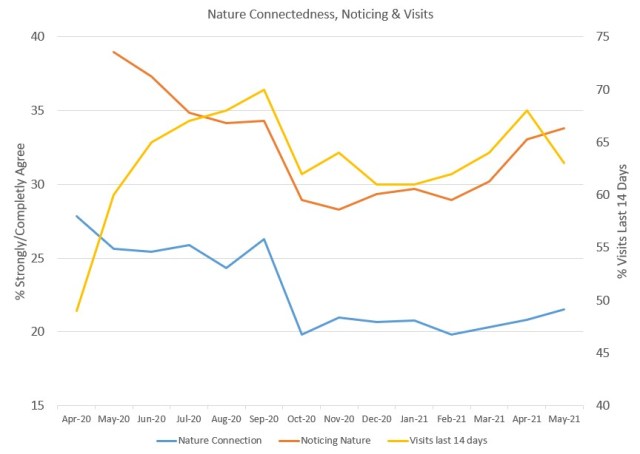

The ‘firmer ground’ of contact goes well beyond psychologists to policy where the focus is often physical access, rather than emotional or meaningful access to nature. As discussed later, for the much needed new relationship with nature, perhaps there’s a need for a new language of connection and access. The science of nature connectedness is more recent than the large body of research into contact with nature, but as I’ve noted previously, contact is easier to measure and to maximise benefits we must ensure research based on metrics that are more straightforward to measure do not dominate policy recommendations. The data to support the important role of nature connectedness in wellbeing is building though. In addition to the specific nature connectedness and wellbeing reviews above, three recent population surveys (1, 2 & 3) directly compare contact and connection with nature. This shows that for mental wellbeing outcomes, nature connection can matter more than time in nature, with empirical work showing the causal link.

It is also interesting that the review discusses comparisons of wellbeing (such as life satisfaction and eudemonic wellbeing), ‘affect balance’ (a topic that is often overlooked and I discuss here) and relationship to income. Similar there’s been nature connectedness research in these areas, from the benefits to both feeling good and functioning well, to how nature connectedness is a strong predictor of eudemonic wellbeing – four times greater than socio economic status.

When presenting options for change, the review again distinguishes between contact with nature and connectedness with nature – the need to take something away from nature contact and internalise it – from a pathways to nature connectedness perspective, to find meaning. The review also states that “contact with the natural world is a means to furthering personal well-being, connectedness with Nature is an aspect of well-being itself” – which mirrors our call earlier in 2021 for nature connectedness to be adopted as a metric for wellbeing. Here there is progress with nature connectedness being trialled in the Gallup World Poll, which is also discussed in the review.

In the section on transforming our institutions and systems, the review continues, “Access to green spaces (they are local public goods) can also reduce socio-economic inequalities in health. Interventions to increase people’s contact and connectedness with Nature would not only improve our health and well-being, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that those interventions would also motivate us to make informed choices and demand change” – thereby capturing the essential reciprocal relationship needed for a sustainable future and indirectly referencing the work on the causal link between nature connectedness and both pro-environmental and pro-nature conservation behaviours.

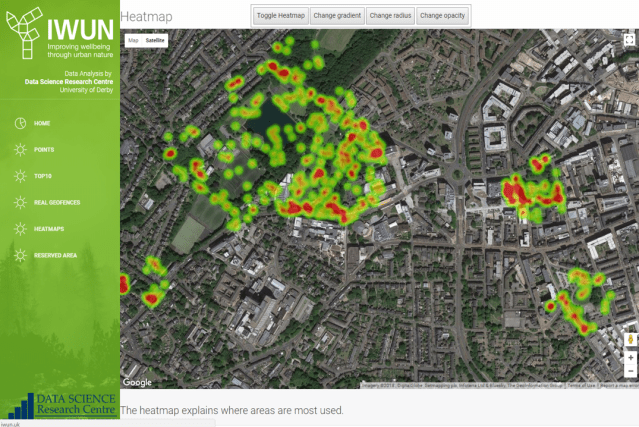

Glimmers of hope for such an approach are identified, in small initiatives for the renewal of urban nature – it is true that examples of programmes to increase both access and nature connectedness are relatively new and recent, but examples can be found, for example 30 Days Wild by The Wildlife Trusts and 50 Things by the National Trust are both informed by the pathways to nature connectedness. More on this work can be found in our recent booklet, Nature & Me. More widely, projects applying the pathways to nature connectedness include the RSPB Scotland nature prescription pilot, the Oak Project, Generation Green and WWT’s Generation Wild. Finally, the connecting people with nature theme of the Government’s Green Recovery Challenge Fund engages applicants with the pathways to nature connectedness, so many more projects are on their way – but is easy to slip back into an anthropocentric approach where access green space is simply provided as a ‘dose of nature’.

Good progress, but the wish in the Dasgupta Review is grand, for a future where citizens can live in peace with nature. The University of Derby’s Nature Connectedness Research Group also has grand visions for a new relationship with nature and proposals for moving from small initiatives to those that increase nature connectedness through transforming institutions and systems – see our recent paper in Ecosystems and People.

Education is a further, and final, option for change that considers nature connectedness with reference to our emotional attachment to nature and appreciation of our place in nature. While the focus on introducing the awe and wonder of nature to children is present, there is reference to teaching knowledge when the research evidence suggests that this isn’t the best route to nature connectedness or ecological behaviour. There is a need to remember that the loss of biodiversity has been overseen by a generation that likely spent more time in nature and had greater knowledge of it. Rather than looking backwards, there is a need for a new relationship with nature where traditional assumptions are challenged and the latest research evidence applied.

Citing the ‘teenage dip’ in nature connectedness, the review states that ‘Connecting with Nature needs to be woven throughout our lives’ and there is need to ‘create an environment in which, from an early age, we are able to connect with Nature’. It is notable that the final section on Transforming our Institutions and Systems is often a manifesto for connecting people with nature and the final paragraph includes the line, ‘Each of these senses is enriched when we recognise that we are embedded in Nature’.

Although the abridged version of the report retains aspects around nature connectedness, the key distinction between contact and connection and the need for connection with nature to be woven throughout our lives, the language of connectedness falls away in the Headline Messages document. There is mention of interventions to enable people to connect with nature for both human and nature’s wellbeing, but education policy is reduced down to environmental education programmes that unless careful designed are known to play a small part in ecological behaviours. Those engaging with the five pages of text in the headline messages will come away with a different feel than when engaging with the much longer abridged version and full report.

From a human-nature connectedness perspective the full Dasgupta Review is very encouraging document. It’s quite up to date and shares much of our thinking around the need for a new relationship with nature. It’s great that a review led by an economist captures this perspective so well.

It’s interesting to consider the Dasgupta Review alongside May’s WHO publication, ‘Nature, biodiversity and health: an overview of interconnections’. It includes a quote from the final paragraph of Dasgupta Review, but that perspective doesn’t run through the overview:

“Biodiversity does not only have instrumental value, it also has existence value – even an intrinsic worth. These senses are enriched when we recognise that we are embedded in Nature. To detach Nature from economics is to imply that we consider ourselves to be external to Her. The fault is not in economics; it lies in the way we have chosen to practise it.”

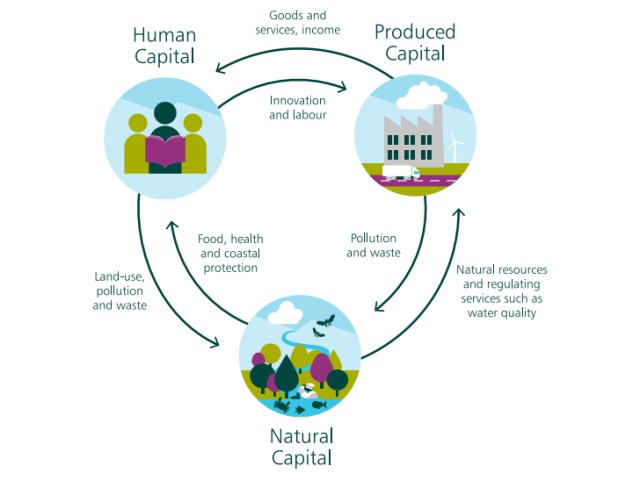

The WHO publication is much shorter, even than the abridged Dasgupta Review. Although the title includes interconnections between nature, biodiversity and health, the summary states that the report ‘provides an overview of the impacts of the natural environment on human health. It presents the ways nature and ecosystems can support and protect health and well-being’. It takes the anthropocentric viewpoint noted in the Dasgupta Review and focuses on the benefits of nature to humans, rather than the interconnections. In contrast to the Dasgupta Review, there is no distinction between contact and connection, with little language around the importance of close human-nature relationships (beyond the quote from the Dasgupta Review). There is mention of non-materials benefits such as spiritual meaning and aesthetic value within a linear figure on Cultural Services, but again the focus is what nature provides for people, rather than a sense of interconnected relationships between people and the rest of nature. The circular interaction between capitals is captured simply in the Dasgupta Review (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Interaction Between the Capitals from Dasgupta, P. (2021), The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. (London: HM Treasury)

When considering access to nature, unlike the Dasgupta Review quote on access above, in the WHO report there’s little on interconnectedness and the opportunity to build access and connection to move beyond the one-way benefits nature provides to human health, towards building a reciprocal human-nature relationship for a sustainable future. Access to nature should provide an opportunity for people to form a close relationship with nature and care for nature – an opportunity to unite human and nature’s wellbeing.

The section on access to nature is short, but to mind access for connection, or facilitating both physical and psychology access to nature is an essential and simple point when considering the interconnections between nature, biodiversity and health. The conclusions of the WHO report focus on the clear need to protect and restore nature, but there is mention of ‘sustainable behaviours that benefit nature and health’, ‘simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits’ and ‘promoting benefits for both human health and the natural environment’ – it’s a shame that’s not a stronger theme throughout.

Previously, I’ve written about the National Parks Landscape Review (Glover Review) and Michael Gove’s speech on a Green Brexit. The Landscape Review included a focus on learning, Michael Gove inferred a distinction between themes such as emotional attachment with nature and science – as policy is rooted in science. Yet there is a science of emotion and connection. The Dasgupta Review embraces the emotional and soulful relationships with nature and recognises the accompanying science. The challenge, as found in the brief Headline Messages document, is retaining and reflecting those essential elements in policy recommendations.

In sum, the WHO report on the interconnections between nature, biodiversity and health sets out the importance of nature for health and thereby the need to protect it. Although a review of the economics of biodiversity, the Dasgupta Review sets out and understands the relationship between people and the rest of nature and how that is key for human and nature’s wellbeing. However, there is still a need for wider acceptance of that message, or a need to find a language of nature connectedness compatible with policy proposals.